Vesak Day is a significant celebration in the Buddhist calendar, marking the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha. This festival is not only a time for spiritual reflection but also a moment to gather with family and friends, sharing traditional foods that embody the essence of Buddhist teachings. The dishes prepared during Vesak Day are deeply rooted in cultural significance, often symbolizing purity, mindfulness, and the interconnectedness of life.

During Vesak Day, a variety of traditional foods are served, each carrying its own cultural and spiritual significance. Common dishes include:

- Rice: Often considered a staple, rice symbolizes sustenance and nourishment.

- Vegetable Curries: These dishes highlight the importance of plant-based diets in Buddhist practice.

- Fresh Fruits: Fruits are not only refreshing but also represent the sweetness of life and enlightenment.

These foods are prepared with care, reflecting the values of mindfulness and gratitude inherent in Buddhist teachings.

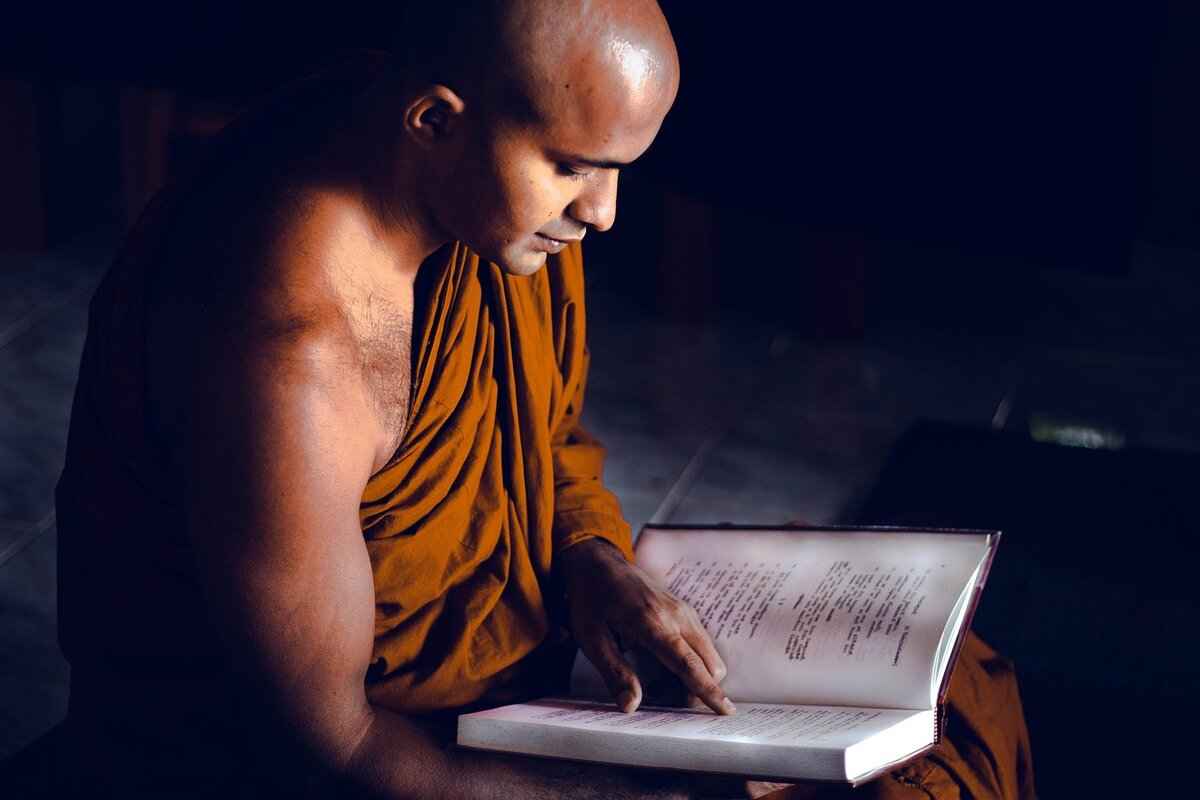

Vegetarianism is a common practice among Buddhists, especially during Vesak Day. This dietary choice stems from a deep sense of compassion and respect for all living beings. By abstaining from meat, participants honor the Buddha’s teachings on non-violence and kindness. This practice also promotes mental clarity and spiritual focus, allowing individuals to connect more deeply with the essence of the festival.

Common vegetarian dishes enjoyed during Vesak Day include:

- Steamed Rice: Often served plain or with light seasoning.

- Stir-Fried Vegetables: Prepared using seasonal vegetables to highlight freshness.

- Fruit Salads: A mix of seasonal fruits, symbolizing abundance and joy.

These dishes are often made with local ingredients, emphasizing simplicity and health, which are central to the celebration.

Food serves as a central element in Vesak Day celebrations, acting as a medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection. Sharing meals reinforces the values of generosity and togetherness, allowing participants to connect with one another and with the teachings of the Buddha. Offerings of food at temples also play a significant role, as they symbolize devotion and gratitude.

Across the globe, different cultures have their unique culinary traditions for Vesak Day. For instance:

- Thailand: Dishes like khao tom (rice soup) are popular, often enjoyed during communal meals.

- China: Buddha’s Delight, a mixed vegetable dish, is commonly served, showcasing a variety of textures and flavors.

These regional variations reflect local ingredients and customs, enriching the celebration with diverse culinary practices.

Many foods consumed during Vesak Day carry profound symbolic meanings. For example, rice and vegetables symbolize purity and simplicity, aligning with key Buddhist teachings on mindfulness and respect for nature. Additionally, offerings made during Vesak Day serve as acts of devotion, reinforcing the connection between individuals and their communities.

Preparing Vesak Day foods at home can be a fulfilling experience. Here are some practical tips:

- Beginner-Friendly Recipes: Start with simple dishes like vegetable stir-fries or steamed rice.

- Incorporate Traditional Elements: Use fresh herbs and seasonal vegetables to enhance the authenticity of your meals.

By engaging in the preparation of these traditional dishes, you can create a meaningful connection to the festival and its teachings.

What Are the Traditional Foods for Vesak Day?

Vesak Day is one of the most significant festivals in Buddhism, celebrating the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha. During this momentous occasion, a variety of traditional foods are prepared and shared among communities, reflecting the rich cultural heritage and spiritual practices of Buddhism. The foods consumed during Vesak Day are not merely sustenance; they are imbued with symbolic meanings that resonate deeply with the teachings of the Buddha.

On Vesak Day, a diverse array of traditional foods is enjoyed, each holding cultural and spiritual significance. These dishes are often prepared with an emphasis on purity and mindfulness, aligning with the core values of Buddhism.

- Rice Dishes: Rice is a staple in many cultures and is often prepared in various forms, such as steamed rice or rice porridge. It symbolizes nourishment and sustenance for both body and spirit.

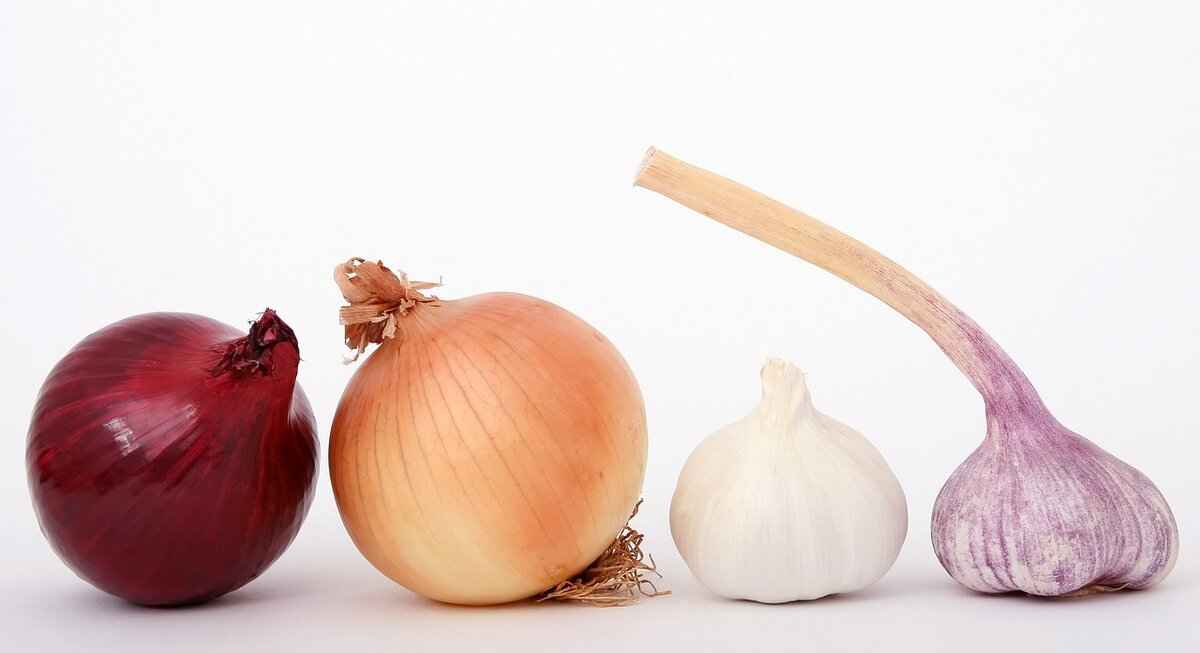

- Vegetable Curries: Colorful vegetable curries are common, showcasing seasonal produce. These dishes not only provide flavor but also reflect the Buddhist principle of compassion towards all living beings.

- Fresh Fruits: Fruits are typically enjoyed for their natural sweetness and health benefits. They symbolize the joy of life and the importance of maintaining a healthy body.

- Traditional Sweets: Desserts such as sweet rice cakes and coconut pudding are popular, representing the sweetness of life and spiritual renewal.

Vegetarianism is a prevalent practice among Buddhists, especially during Vesak Day. The choice to abstain from meat stems from a deep-seated respect for all living beings, reinforcing the values of compassion and non-violence. This dietary choice is not only a reflection of personal beliefs but also a way to honor the Buddha’s teachings.

Common vegetarian dishes served during Vesak Day include:

- Stir-Fried Vegetables: Quick and simple, these dishes often include a variety of local vegetables, emphasizing freshness and seasonal availability.

- Grain-Based Meals: Grains such as quinoa or barley may be used, symbolizing prosperity and abundance.

The preparation of Vesak Day foods typically focuses on simplicity and mindfulness. Ingredients are chosen with care, and cooking methods often highlight the natural flavors without excessive seasoning. This approach reflects the Buddhist practice of being present and appreciating each moment.

Desserts hold a special place during Vesak Day celebrations. Popular choices include:

- Sweet Rice Cakes: These are often made with glutinous rice and filled with sweetened coconut.

- Coconut Pudding: This creamy dessert symbolizes the joy and renewal associated with the festival.

Food plays a central role in Vesak Day celebrations, serving as a medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection. Sharing meals reinforces the values of generosity and togetherness, creating a sense of unity among participants. These communal meals often include offerings made at temples, where food is shared among monks and laypeople alike, embodying the spirit of compassion.

Different cultures have unique culinary traditions for Vesak Day, showcasing local ingredients and customs. For example, in Thailand, the dish ‘khao tom’ is often served, while in China, ‘Buddha’s delight’ is a popular choice. These regional variations highlight the diversity of Buddhist culinary practices and the adaptability of the festival to local traditions.

Many foods consumed during Vesak Day carry symbolic meanings that reflect Buddhist philosophy. For instance, rice symbolizes purity and simplicity, while fresh vegetables represent the interconnectedness of life. Each dish serves as a reminder of the teachings of the Buddha and the importance of mindfulness in daily life.

Preparing Vesak Day foods at home can be a fulfilling experience. Simple recipes, such as vegetable stir-fries and rice dishes, can help capture the essence of the celebration. Incorporating traditional elements like fresh herbs and seasonal vegetables can enhance the authenticity of your Vesak Day meals, allowing for a deeper connection to the festival’s cultural roots.

Why Are Vegetarian Dishes Popular on Vesak Day?

Vegetarianism holds a significant place in Buddhist culture, particularly during the celebration of Vesak Day. This day marks the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha, and is a time for reflection, compassion, and mindfulness. The choice to embrace a vegetarian diet during this sacred occasion stems from deep-rooted values that resonate with the core teachings of Buddhism.

One of the primary reasons for the popularity of vegetarian dishes on Vesak Day is the emphasis on compassion for all living beings. Buddhists believe in the principle of ahimsa, or non-violence, which extends to all forms of life. By choosing vegetarian options, practitioners express their respect for animals and the interconnectedness of life, aligning their dietary choices with their spiritual beliefs.

Additionally, vegetarianism during Vesak Day serves as a reminder of the impermanence of life. Consuming plant-based foods encourages mindfulness and appreciation of the natural world, fostering a deeper connection to the environment and the cycle of life. This practice not only nourishes the body but also nourishes the spirit, allowing individuals to reflect on their actions and their impact on the world around them.

What Types of Vegetarian Dishes Are Common?

- Rice Dishes: Rice is a staple in many cultures and often serves as the base for various vegetarian curries and stir-fries.

- Fresh Vegetables: Seasonal vegetables are prepared in a variety of ways, highlighting their natural flavors and nutritional benefits.

- Fruits: Fresh fruits are commonly enjoyed as a symbol of abundance and the sweetness of life.

How Are These Dishes Prepared?

Preparation methods for vegetarian dishes during Vesak Day often emphasize simplicity and freshness. Local ingredients are prioritized, and meals are prepared with care and attention to detail. This approach not only enhances the flavor but also reflects the values of mindfulness and gratitude that are central to Buddhist teachings.

What Role Does Food Play in Vesak Day Celebrations?

Food plays a central role in Vesak Day celebrations, serving as a medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection. Sharing meals with family and friends fosters a sense of togetherness and reinforces the values of generosity and compassion. The act of preparing and sharing vegetarian dishes becomes a form of devotion, allowing participants to express their gratitude and respect for life.

How Do Different Cultures Celebrate Vesak Day with Food?

Across various cultures, the celebration of Vesak Day is marked by unique culinary traditions that reflect local ingredients and customs. For instance, in Thailand, the dish ‘khao tom’ is a popular choice, while in China, ‘buddha’s delight’ is commonly served. These regional variations showcase the diversity of Buddhist culinary practices and the adaptability of vegetarianism within different cultural contexts.

What Are the Symbolic Meanings Behind Vesak Day Foods?

Many foods consumed during Vesak Day carry profound symbolic meanings. Ingredients such as rice, vegetables, and fruits symbolize purity, simplicity, and the interconnectedness of life. By consuming these foods, practitioners align their actions with key Buddhist teachings, reinforcing their commitment to mindfulness and respect for nature.

In summary, the popularity of vegetarian dishes during Vesak Day is deeply intertwined with the principles of compassion, mindfulness, and respect for all living beings. By embracing vegetarianism on this significant occasion, Buddhists not only honor their spiritual beliefs but also cultivate a deeper connection to the world around them.

What Types of Vegetarian Dishes Are Common?

Vesak Day is a time of reflection, joy, and celebration for Buddhists around the world. During this significant festival, various traditional foods are prepared, each holding deep cultural and spiritual significance. Among these, vegetarian dishes are particularly prominent, embodying the core values of compassion and mindfulness that are central to Buddhist teachings.

Common vegetarian dishes during Vesak Day include a delightful array of rice, curries, and fresh fruits. These foods are not merely sustenance; they are prepared with meticulous care, reflecting the values of mindfulness and gratitude inherent in Buddhist teachings.

- Rice: A staple in many cultures, rice is often cooked in various ways, such as steamed, fried, or as part of a savory dish. It symbolizes prosperity and nourishment.

- Curry: Rich and flavorful, curries can be made with a variety of vegetables and spices. They represent the diversity of life and the importance of harmony in flavors, echoing the interconnectedness of all beings.

- Fresh Fruits: Fruits are a symbol of purity and natural beauty. They are often offered in their natural state, showcasing the beauty of simplicity and the importance of gratitude for nature’s bounty.

Beyond these staples, the preparation of these dishes often emphasizes freshness and local ingredients. This not only supports local farmers but also enhances the flavor and nutritional value of the meals. The act of cooking and sharing these dishes during Vesak Day serves as a reminder of the importance of community and connection.

Vegetarianism is deeply rooted in Buddhist philosophy. During Vesak Day, many Buddhists choose to abstain from meat as a demonstration of compassion for all living beings. This practice aligns with the core Buddhist belief in the sanctity of life and the principle of ahimsa, or non-violence.

By consuming vegetarian dishes, Buddhists not only honor this belief but also engage in a practice of mindfulness. Each bite becomes an opportunity to reflect on the interconnectedness of life and the gratitude owed to the earth for its resources.

The preparation of vegetarian dishes for Vesak Day often incorporates traditional methods that highlight the ingredients’ natural flavors. For example, many families may opt for steaming or lightly sautéing vegetables to retain their nutrients and vibrant colors. The use of herbs and spices adds depth to the dishes while keeping them wholesome.

Moreover, communal cooking is a cherished practice during this festival. Families and friends gather to prepare meals together, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose. This collaborative spirit enhances the overall experience of Vesak Day, making the meals even more meaningful.

Desserts during Vesak Day also hold special significance, often representing joy and spiritual renewal. Popular choices include sweet rice cakes and coconut pudding, which symbolize the sweetness of life and the joy of the festival. These treats are often shared among family and friends, reinforcing the values of sharing and togetherness.

In conclusion, the vegetarian dishes served during Vesak Day are more than just food; they are a reflection of Buddhist values and beliefs. From rice and curries to fresh fruits and desserts, each dish plays a vital role in the celebration, embodying the principles of compassion, mindfulness, and community.

How Are These Dishes Prepared?

When it comes to the preparation of traditional dishes for Vesak Day, the emphasis is often on simplicity and freshness. This festival, which commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and death of Buddha, encourages the use of local ingredients to create meals that are not only delicious but also nourishing for both the body and the spirit.

The preparation methods reflect the core values of Buddhism, emphasizing the importance of mindfulness and gratitude. Many dishes are crafted with care, ensuring that each ingredient is treated with respect. This approach aligns with the Buddhist principle of ahimsa, or non-violence, which extends to how food is sourced and prepared.

- Rice: A staple in many Asian diets, rice symbolizes purity and sustenance.

- Vegetables: Seasonal and locally sourced vegetables are preferred, showcasing the bounty of nature.

- Fruits: Fresh fruits not only add sweetness but also represent the joy of life.

Preparation techniques vary by region but often include steaming, boiling, and stir-frying. These methods preserve the natural flavors and nutrients of the ingredients:

- Steaming: This technique is popular for cooking rice and vegetables, allowing them to retain their vibrant colors and essential nutrients.

- Boiling: Used for soups and broths, boiling helps create warm, comforting dishes that bring people together.

- Stir-frying: A quick cooking method that enhances the flavors of vegetables while keeping them crisp and fresh.

Different cultures bring unique flavors and techniques to Vesak Day meals. For instance, in Thailand, dishes like khao tom (rice soup) are commonly prepared, while in China, Buddha’s delight is a popular vegetarian dish. These regional variations reflect local ingredients and culinary traditions, enriching the Vesak celebration.

Food preparation for Vesak Day is often a communal effort. Families and friends gather to cook together, reinforcing bonds and sharing the joy of the festival. This collective experience not only enhances the flavors of the dishes but also embodies the spirit of sharing and generosity that is central to Buddhist teachings.

For those wishing to participate in Vesak Day celebrations at home, preparing traditional dishes can be a rewarding experience. Here are some practical tips:

- Start with Simple Recipes: Focus on easy-to-make dishes like vegetable stir-fries or rice with seasonal vegetables.

- Use Fresh Ingredients: Visit local markets to find the freshest produce available, enhancing the quality of your meals.

- Incorporate Traditional Elements: Use herbs and spices that are traditional to your culture, adding authenticity to your dishes.

In conclusion, the preparation of Vesak Day foods is a meaningful practice that emphasizes simplicity, freshness, and community. By using local ingredients and traditional methods, individuals can create meals that not only nourish the body but also uplift the spirit, embodying the essence of this significant Buddhist festival.

What Are Some Popular Desserts for Vesak Day?

Vesak Day is a significant celebration in the Buddhist calendar, marking the birth, enlightenment, and passing of Buddha. As part of this spiritual observance, various traditional foods are prepared and enjoyed, each carrying its own cultural and symbolic significance. Among these, desserts play a special role, often representing the sweetness of life and the joy of spiritual renewal.

During Vesak Day, a variety of desserts are enjoyed, with sweet rice cakes and coconut pudding being particularly popular. These dishes are not just treats; they symbolize important aspects of the celebration. The sweetness of these desserts represents the sweetness of life and the joy that comes from spiritual enlightenment.

- Sweet Rice Cakes: Often made from glutinous rice, these cakes are sometimes filled with sweetened mung bean paste or coconut. They are steamed to perfection, offering a soft and chewy texture that delights the palate.

- Coconut Pudding: This creamy dessert is made from coconut milk, sugar, and agar-agar. It is often served chilled, providing a refreshing end to the meal and symbolizing purity and simplicity.

- Fruit Offerings: Fresh fruits such as bananas, mangoes, and lychees are also common. These fruits are not only delicious but also represent the abundance of nature and the interconnectedness of life.

Desserts play a crucial role in the Vesak Day celebrations, serving as a medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection. Sharing these sweet treats among family and friends reinforces the values of generosity and compassion that are central to Buddhist teachings. The act of offering food, especially sweets, is a way to express gratitude and appreciation for life’s blessings.

The preparation of Vesak Day desserts emphasizes simplicity and freshness. Many recipes utilize local and seasonal ingredients, ensuring that the dishes are not only delicious but also nourishing. For instance, the use of fresh coconut in puddings highlights the importance of using natural ingredients, aligning with the Buddhist principle of living in harmony with nature.

- Mindful Cooking: Preparing these desserts often involves a mindful approach, where cooks pay attention to each step, from selecting ingredients to the final presentation.

- Community Involvement: In many cultures, families and friends gather to prepare these dishes together, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose.

The desserts enjoyed during Vesak Day are rich in symbolism. For example, the sweetness of rice cakes and puddings represents the joy of spiritual renewal and the sweetness of enlightenment. Each bite serves as a reminder of the teachings of Buddha, encouraging mindfulness and appreciation for the present moment.

Furthermore, these desserts often reflect the diversity of Buddhist cultures around the world. In different regions, variations of these sweets may incorporate local flavors and ingredients, showcasing the rich tapestry of Buddhist culinary traditions.

Making traditional Vesak Day desserts at home can be a rewarding experience. Here are some simple recipes to try:

- Sweet Rice Cake Recipe: Combine glutinous rice flour with water and sugar, knead into a dough, fill with sweetened mung bean paste, and steam until cooked.

- Coconut Pudding Recipe: Mix coconut milk, sugar, and agar-agar in a pot, bring to a boil, pour into molds, and refrigerate until set.

By incorporating these traditional desserts into your Vesak Day celebrations, you can engage more deeply with the festival’s cultural roots and enjoy the sweet flavors that symbolize the essence of this important occasion.

What Role Does Food Play in Vesak Day Celebrations?

Food is not merely a sustenance source during Vesak Day; it embodies the spirit of the celebration itself. This significant Buddhist festival, which marks the birth, enlightenment, and passing of the Buddha, emphasizes the importance of community, compassion, and mindfulness. As such, the role of food in Vesak Day celebrations transcends mere consumption, serving as a vital medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection.

During Vesak Day, food acts as a social glue that brings people together. Families and friends gather to prepare and share meals, reinforcing their connections and fostering a sense of unity. The act of cooking and sharing food is deeply rooted in Buddhist teachings, which emphasize generosity and compassion. Communal meals are often organized in temples, where devotees offer food to monks and share with one another, creating an atmosphere of togetherness.

In addition to its social aspects, food during Vesak Day carries profound spiritual significance. Many dishes are prepared with mindfulness and care, reflecting the values of the Buddhist path. The act of offering food to the Buddha and sharing it with others is seen as a form of devotion and gratitude. These offerings symbolize the abundance of blessings and the interconnectedness of all living beings, reminding participants of the importance of living in harmony with nature and each other.

Vegetarianism is a common practice among Buddhists, particularly during Vesak Day. This dietary choice stems from the teachings of the Buddha, who advocated for compassion towards all living beings. By consuming vegetarian dishes, participants honor this principle and demonstrate respect for life. Typical vegetarian offerings include rice, fresh vegetables, and fruits, all prepared with an emphasis on simplicity and purity, echoing the essence of mindfulness.

- Rice Dishes: Often served as a staple, rice symbolizes nourishment and abundance.

- Curry Varieties: These flavorful dishes are made with seasonal vegetables and spices, representing the richness of life.

- Fresh Fruits: Fruits are offered as a symbol of sweetness in life and the joy of spiritual renewal.

Offerings made during Vesak Day are not just about food; they are acts of devotion that reinforce the connection between individuals and their communities. Each dish presented at the altar is a reminder of the importance of sharing and generosity. The ritual of offering food serves as a way to express gratitude for the Buddha’s teachings and to cultivate a spirit of selflessness.

The culinary traditions associated with Vesak Day vary across cultures, reflecting local ingredients and customs. For instance, in Thailand, the dish ‘khao tom’ (rice soup) is commonly served, while in China, ‘Buddha’s delight’ (a vegetarian stir-fry) is popular. Each culture’s unique dishes contribute to the rich tapestry of Vesak celebrations, showcasing the diversity of Buddhist culinary practices.

Many foods consumed during Vesak Day carry symbolic meanings, representing various aspects of Buddhist philosophy. Ingredients like rice, vegetables, and fruits symbolize purity, simplicity, and the interconnectedness of life. This alignment with Buddhist teachings enhances the spiritual experience of the festival, allowing participants to reflect on their beliefs while enjoying the communal aspects of the celebration.

In summary, food plays an essential role in Vesak Day celebrations. It fosters community bonding, serves as a medium for spiritual reflection, and embodies the core values of generosity and compassion. Through shared meals and mindful offerings, participants engage deeply with the festival’s significance, creating lasting memories and reinforcing their connections to each other and their faith.

How Do Different Cultures Celebrate Vesak Day with Food?

Vesak Day, also known as Buddha Purnima, is a momentous occasion in the Buddhist calendar, celebrated by millions around the world. This festival commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha, and food plays a pivotal role in the celebrations. Different cultures have unique culinary traditions for Vesak Day, reflecting local ingredients and customs. This section examines how various Buddhist communities celebrate with distinctive dishes.

Across the globe, Buddhist communities showcase their cultural heritage through the foods they prepare for Vesak Day. These culinary traditions not only highlight local ingredients but also embody the spiritual essence of the festival. For instance, in Thailand, the festival is marked by the preparation of khao tom, a traditional rice soup often served with fresh herbs and vegetables, symbolizing purity and simplicity.

- Thailand: In Thailand, khao tom is a staple, often accompanied by fresh fruits and herbal dishes that emphasize the importance of freshness and local produce.

- China: Chinese Buddhists celebrate with Buddha’s Delight, a vegetarian dish made with a variety of vegetables and tofu, symbolizing the abundance of life and the practice of compassion.

- Sri Lanka: In Sri Lanka, traditional sweets like kavum (oil cakes) are prepared, representing the joy of celebration and community bonding.

- Japan: Japanese Buddhists may partake in oshiruko, a sweet red bean soup, which is often enjoyed during the festival as a symbol of warmth and community.

During Vesak Day, food choices are greatly influenced by the festive atmosphere. Many Buddhist communities engage in communal meals, where dishes are shared among family and friends. This practice not only fosters a sense of community but also reinforces the values of generosity and sharing. Offerings made at temples often include a variety of foods, symbolizing abundance and gratitude. These communal feasts allow participants to reflect on the teachings of the Buddha while enjoying the flavors of their cultural heritage.

The foods consumed during Vesak Day carry significant symbolic meanings. For instance, rice is often seen as a symbol of fertility and prosperity, while fruits represent the sweetness of life and spiritual growth. Dishes are typically prepared with mindfulness, reflecting the importance of intention in Buddhist practice. Each ingredient is chosen not only for its taste but also for its spiritual significance, aligning with the core teachings of Buddhism regarding respect for nature and all living beings.

For those looking to celebrate Vesak Day at home, preparing traditional dishes can be a rewarding experience. Simple recipes such as vegetable stir-fries or rice dishes can easily capture the essence of the festival. Incorporating fresh herbs and seasonal ingredients can enhance the authenticity of your meals. Sharing these dishes with family and friends can foster a sense of togetherness and reflection on the teachings of the Buddha.

In conclusion, the culinary traditions of Vesak Day vary widely across cultures, each offering a unique perspective on the celebration of the Buddha’s life and teachings. By exploring these diverse foods, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for the festival but also an understanding of the rich tapestry of Buddhist culinary practices around the world.

What Are Some Regional Variations in Vesak Foods?

Vesak Day is a time of reflection and celebration for Buddhists around the world. As this significant festival honors the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha, the foods prepared and consumed during this time hold deep cultural and spiritual meanings. Among the many culinary traditions, regional variations reflect the rich diversity of Buddhist practices globally.

Throughout Asia, different cultures celebrate Vesak Day with unique dishes that embody local flavors and ingredients. For instance, in Thailand, a popular dish known as khao tom is often served. This comforting rice soup, typically made with fragrant jasmine rice and a variety of vegetables, symbolizes nourishment and simplicity. It is often enjoyed as a communal dish, reinforcing the importance of sharing during this sacred time.

In contrast, Chinese Buddhist communities prepare a dish called Buddha’s Delight or Luohan Zhai. This flavorful stir-fry combines a medley of vegetables, tofu, and sometimes, mushrooms. The dish is not only delicious but also represents the values of compassion and respect for all living beings, aligning with the teachings of the Buddha. The ingredients often vary by region, showcasing local produce and culinary preferences.

Other notable regional dishes include:

- Vietnam: In Vietnam, Chay dishes are prevalent during Vesak, featuring a variety of vegetarian options, including vegetable pho and spring rolls, symbolizing purity and mindfulness.

- Sri Lanka: Sri Lankans often prepare kiribath (milk rice) during Vesak, which is served with a variety of sambols and curries, representing abundance and the sharing of blessings.

- Japan: In Japan, oshiruko, a sweet red bean soup with mochi, is enjoyed, symbolizing sweetness in life and the joy of spiritual renewal.

These regional dishes not only highlight the diversity of ingredients and flavors but also reflect the local customs and traditions that shape how communities celebrate Vesak. Each dish carries a story and a purpose, reinforcing the values of mindfulness, gratitude, and compassion that are central to Buddhist teachings.

The festivities surrounding Vesak Day significantly influence the food choices made by communities. Many families come together to prepare and share meals, fostering a sense of community and togetherness. Offerings made at temples often include a variety of vegetarian dishes, emphasizing the importance of sharing food as an act of devotion and unity.

In many cultures, the preparation of food for Vesak is seen as a spiritual practice. The act of cooking is performed with mindfulness, and the ingredients are chosen carefully to reflect the values of purity and simplicity. This attention to detail not only enhances the flavors but also deepens the spiritual connection to the festival.

Moreover, these communal meals provide an opportunity for individuals to reflect on the teachings of the Buddha, reinforcing the importance of compassion and generosity. As families and communities gather to enjoy these meals, they celebrate not just the festival itself but also the bonds that unite them.

Many of the foods consumed during Vesak Day carry profound symbolic meanings. Ingredients like rice, which is a staple in many Asian cultures, symbolize nourishment and the interconnectedness of life. Fresh vegetables and fruits represent purity and the cycle of life, while sweets signify the joy and sweetness of spiritual renewal.

In conclusion, the regional variations in Vesak foods highlight the rich tapestry of Buddhist culinary practices across different cultures. From the comforting khao tom in Thailand to the flavorful Buddha’s Delight in China, each dish serves as a reminder of the values that underpin this significant celebration. As Buddhists around the world come together to share these meals, they not only honor the Buddha’s teachings but also strengthen their communal ties and reflect on the deeper meanings of their culinary traditions.

How Do Festivities Influence Food Choices?

Festivals are deeply woven into the fabric of many cultures, and the choices of food during these celebrations often reflect the values and traditions of the community. During Vesak Day, which commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and passing of the Buddha, food choices take on a significant role. The communal aspect of this festival emphasizes the importance of sharing, which is a core tenet of Buddhist teachings.

Communal meals are a vital part of Vesak Day celebrations. Families and communities come together to prepare and share meals, reinforcing the bonds of togetherness and compassion. This practice not only nourishes the body but also the spirit, as participants engage in acts of generosity and kindness. Sharing food is a way to honor the Buddha’s teachings on interconnectedness and the importance of community.

During Vesak, many Buddhists make offerings at temples, which often include food. These offerings are not merely acts of devotion but are imbued with deep spiritual significance. They symbolize gratitude and respect for the teachings of the Buddha. By offering food, practitioners express their commitment to the Buddhist path and their desire to cultivate a sense of community. The act of sharing these offerings with fellow devotees further emphasizes the principles of generosity and compassion.

Traditional Vesak Day foods often include a variety of vegetarian dishes, such as:

- Rice: A staple in many Buddhist cultures, rice symbolizes sustenance and purity.

- Vegetable Curries: These dishes are prepared with fresh, seasonal ingredients, reflecting the importance of mindfulness in food choices.

- Fresh Fruits: Fruits are often seen as symbols of abundance and the sweetness of life.

These foods are prepared with care and intention, aligning with the values of mindfulness and gratitude that are central to Buddhist practice.

The festive atmosphere of Vesak Day encourages individuals to embrace vegetarianism, even if they are not strict vegetarians year-round. The choice to consume plant-based meals during this time reflects a commitment to compassion for all living beings. This dietary preference is not only a personal choice but also a communal one, as many families and groups opt for vegetarian menus to align with the spirit of the celebration.

Different cultures celebrate Vesak Day with unique culinary traditions, showcasing regional ingredients and customs. For instance:

- In Thailand, khao tom (rice soup) is a popular dish that reflects local flavors and traditions.

- In China, Buddha’s delight is a vegetarian dish that highlights the diversity of Buddhist culinary practices.

These variations not only enrich the festival but also allow practitioners to connect with their cultural heritage while celebrating the teachings of the Buddha.

The food consumed during Vesak Day is more than just sustenance; it is a means of expressing spiritual devotion and fostering community spirit. By choosing to share meals, individuals participate in a collective experience that honors the teachings of the Buddha. This practice reinforces the values of mindfulness, compassion, and generosity, making the celebration a profound expression of faith and community.

In summary, the choices of food during Vesak Day are deeply influenced by the festival’s spirit of sharing and community. Through communal meals and offerings, participants engage in acts of kindness and reflection, embodying the teachings of the Buddha while celebrating the interconnectedness of all beings.

What Are the Symbolic Meanings Behind Vesak Day Foods?

Vesak Day, a significant celebration in the Buddhist calendar, not only marks the birth, enlightenment, and passing of the Buddha but also emphasizes the importance of food in expressing spiritual values and communal harmony. The foods consumed during this festival are rich in symbolic meanings, reflecting various aspects of Buddhist philosophy and teachings.

During Vesak Day, the choice of food goes beyond mere sustenance; it embodies the principles of compassion, mindfulness, and gratitude. Each dish serves as a reminder of the teachings of the Buddha and the interconnectedness of all beings.

- Rice: Often considered a staple in many cultures, rice symbolizes nourishment and the essence of life. It represents the Buddha’s teachings on simplicity and the importance of sustaining life.

- Vegetables: Fresh, seasonal vegetables signify purity and mindfulness, encouraging individuals to appreciate the gifts of nature and the importance of consuming wholesome foods.

- Fruits: Fruits, especially those that are sweet, symbolize the joy of life and the spiritual renewal that comes with enlightenment. They are often offered in gratitude and as an expression of abundance.

Offerings made during Vesak Day are not just acts of devotion; they are expressions of gratitude and compassion towards all living beings. By presenting food at temples, practitioners reinforce their connection to the community and their commitment to the Buddhist path.

These offerings symbolize the act of sharing, reflecting the Buddha’s teachings on generosity and selflessness. They serve as a reminder of the importance of community and the interdependence of all life.

Across various cultures, the foods associated with Vesak Day carry unique meanings and interpretations. For example, in Thailand, the dish khao tom (a rice soup) is served, symbolizing warmth and comfort. In China, the dish Buddha’s Delight is prepared, representing a medley of vegetables that reflect harmony and balance.

These regional variations highlight how local ingredients and customs shape the culinary landscape of Vesak Day, while still adhering to the core values of Buddhism.

Food plays a central role in the celebrations of Vesak Day, acting as a medium for community bonding and spiritual reflection. The act of sharing meals fosters a sense of togetherness and reinforces the values of generosity and compassion among participants.

During communal meals, individuals come together to reflect on the teachings of the Buddha, sharing stories and experiences that deepen their understanding of Buddhist principles. This practice not only nourishes the body but also enriches the spirit.

To fully embrace the symbolism of Vesak Day foods, one can start by incorporating traditional elements into their meals. Using fresh, local ingredients and preparing dishes with care can enhance the spiritual significance of the food. Simple recipes such as vegetable stir-fries or rice dishes allow individuals to connect with the essence of the celebration.

By understanding the deeper meanings behind the foods consumed during Vesak Day, individuals can enrich their own celebrations and foster a greater appreciation for the teachings of the Buddha.

How Do Ingredients Reflect Buddhist Teachings?

In the celebration of Vesak Day, the foods consumed are not merely sustenance; they embody spiritual significance and reflect the core teachings of Buddhism. Ingredients such as rice, vegetables, and fruits serve as symbols of purity, simplicity, and the interconnectedness of life. These elements align with the teachings of mindfulness and respect for nature that are central to Buddhist philosophy.

Rice is often referred to as the “staff of life” in many cultures, and in Buddhism, it holds a special place. It symbolizes nourishment and abundance, reflecting the idea that all beings are interconnected through the cycle of life. During Vesak Day, rice is prepared in various forms, such as steamed, boiled, or as part of rice cakes, to signify the importance of sharing and community.

Vegetables are a crucial component of Buddhist meals, representing health and vitality. They are often grown in local gardens, emphasizing the connection to the earth and the importance of environmental stewardship. By consuming fresh vegetables, Buddhists practice gratitude for nature’s bounty and acknowledge the effort involved in food cultivation.

Fruits, particularly those that are seasonal and local, symbolize spiritual renewal and the sweetness of life. On Vesak Day, fruits are often offered at altars as a gesture of respect and gratitude. Their vibrant colors and natural sweetness remind practitioners of the joy and beauty inherent in the world around them. Additionally, fruits like bananas and mangoes are frequently used in traditional dishes, adding both flavor and nutritional value.

Mindfulness is a fundamental aspect of Buddhism, and this is reflected in the way food is prepared for Vesak Day. The process of cooking is approached with care and attention, transforming it into a meditative practice. By focusing on the ingredients and the act of cooking, individuals cultivate a deeper connection to their meals and the teachings of the Buddha.

During Vesak Day, food offerings made at temples and community gatherings serve as a means of strengthening community bonds. These acts of generosity not only nourish the body but also foster a sense of belonging and shared purpose among participants. The act of sharing food is a profound expression of compassion, reinforcing the interdependence of all beings.

Buddhist teachings emphasize respect for all living beings, which is reflected in the preference for vegetarian and plant-based diets. By choosing ingredients that are sustainable and ethically sourced, Buddhists align their dietary practices with their spiritual beliefs. This commitment to environmental sustainability is increasingly relevant in today’s world, where food choices can significantly impact the planet.

Individuals can incorporate the principles of Buddhist teachings into their own cooking practices by focusing on local, seasonal ingredients. Preparing meals mindfully and sharing them with family and friends can create a sense of community and connection. Additionally, exploring traditional recipes and understanding their significance can deepen one’s appreciation for the cultural heritage of Vesak Day.

In summary, the ingredients used in Vesak Day celebrations are rich in symbolism and meaning, reflecting the profound teachings of Buddhism. Through the mindful selection and preparation of rice, vegetables, and fruits, practitioners not only honor their spiritual beliefs but also promote a deeper connection to the world around them.

What Do Offerings Represent in Buddhist Tradition?

Offerings made during Vesak Day are deeply rooted in Buddhist tradition and serve as significant acts of devotion and gratitude. This sacred day commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and passing of the Buddha, making it a time for reflection and connection. The act of making offerings not only reinforces the individual’s relationship with the community but also highlights the spiritual importance of food in Buddhist practice.

In Buddhism, offerings are more than mere gifts; they symbolize gratitude and respect for the teachings of the Buddha. These acts are seen as a way to cultivate a sense of mindfulness and appreciation for what one has. By offering food, flowers, and incense, practitioners express their devotion and seek to purify their minds and hearts.

During Vesak Day, communal offerings encourage a sense of belonging and togetherness. When individuals come together to share food and resources, they strengthen their bonds and reinforce the values of generosity and compassion that are central to Buddhist teachings. This shared experience not only enhances the celebration but also deepens the spiritual connection among participants.

- Food: Vegetarian dishes, fruits, and sweets are often offered, symbolizing purity and mindfulness.

- Flowers: Fresh flowers represent the beauty of life and the impermanence of existence.

- Incense: Burning incense signifies the aspiration for enlightenment and the purification of the mind.

Food plays a critical role in Buddhist offerings as it embodies the spirit of sharing and nourishing both body and soul. Each dish is prepared with care and intention, reflecting the values of mindfulness and respect for nature. The act of offering food is not just a ritual; it is a means of connecting with the divine and honoring the teachings of the Buddha.

The ingredients used in offerings often carry profound meanings. For instance, rice symbolizes sustenance and life, while fruits represent the sweetness of spiritual practice. By choosing these elements, practitioners align their offerings with the core principles of Buddhism, such as interconnectedness and simplicity. This mindfulness in selection and preparation serves as a reminder of the importance of living in harmony with all beings.

In Buddhism, the intention behind an offering is paramount. It is believed that the purity of one’s heart and mind can transform a simple act into a profound expression of devotion. When making offerings, practitioners focus on their intentions, aiming to cultivate compassion and gratitude. This focus on intention enhances the spiritual significance of the offerings and deepens the connection to the Buddha’s teachings.

Engaging in the practice of making offerings can significantly enhance one’s spiritual journey. It encourages self-reflection and a deeper understanding of the values that Buddhism promotes. By participating in this tradition, individuals can foster a sense of community, cultivate mindfulness, and express their devotion in meaningful ways.

In summary, offerings made during Vesak Day are much more than ceremonial acts; they are profound expressions of devotion, community, and spiritual significance. By understanding the deeper meanings behind these offerings, practitioners can enrich their spiritual practice and strengthen their connections with others.

How Can You Prepare Vesak Day Foods at Home?

Preparing Vesak Day foods at home can be a fulfilling experience that allows individuals and families to engage with the spiritual and cultural significance of this important Buddhist celebration. By cooking traditional dishes, you not only honor the teachings of Buddha but also create an opportunity for mindfulness and gratitude within your home. This section provides practical tips and recipes that allow anyone to participate in the celebration meaningfully.

When preparing Vesak Day foods, it’s essential to focus on fresh and wholesome ingredients that reflect the values of purity and simplicity. Common ingredients include:

- Rice: A staple in many cultures, symbolizing abundance and nourishment.

- Fresh Vegetables: Seasonal vegetables represent health and vitality.

- Fruits: Sweet fruits are often used in desserts, symbolizing joy and sweetness in life.

- Herbs: Fresh herbs enhance flavor and connect dishes to nature.

For those new to cooking or looking for simple recipes, here are a few beginner-friendly options:

- Vegetable Stir-Fry: A quick and colorful dish that can be made with any seasonal vegetables. Stir-fry them in a bit of oil, add soy sauce, and serve over rice.

- Simple Coconut Rice: Cook rice with coconut milk for a rich and creamy side dish. This pairs well with various curries.

- Fresh Fruit Salad: Combine a variety of fruits such as mango, papaya, and bananas, and drizzle with a bit of lime juice for a refreshing dessert.

Incorporating traditional elements into your Vesak Day meals can enhance the authenticity and connection to the celebration. Here are some tips:

- Use Local Ingredients: Sourcing local produce not only supports your community but also aligns with the Buddhist principle of respecting nature.

- Emphasize Presentation: Arrange your dishes thoughtfully, as presentation plays a significant role in Buddhist culture, symbolizing respect and mindfulness.

- Offer Dishes to Family and Friends: Sharing food is a core aspect of Vesak Day, so consider inviting loved ones to partake in the meal.

Preparation methods often emphasize simplicity and freshness. Here are some techniques to consider:

- Steaming: A healthy cooking method that retains nutrients, perfect for vegetables.

- Stir-Frying: Quick cooking at high heat helps to preserve the color and crunch of vegetables.

- Boiling: Great for preparing rice or soups, allowing for easy incorporation of various ingredients.

To deepen the significance of your Vesak Day celebration, consider the following:

- Mindful Cooking: Engage in the cooking process with mindfulness, focusing on each step and appreciating the ingredients.

- Incorporate Rituals: Light candles or incense while cooking to create a peaceful atmosphere.

- Reflect on Buddha’s Teachings: Take a moment before meals to reflect on the teachings of Buddha and express gratitude for the food.

By preparing Vesak Day foods at home, you can create a meaningful celebration that honors Buddhist traditions while fostering a sense of community and togetherness. Enjoy the process of cooking, and remember that each dish is a reflection of your care and intention.

What Are Some Easy Recipes for Beginners?

Celebrating Vesak Day at home can be a rewarding experience, especially when you prepare dishes that are both meaningful and easy to make. For those who are new to cooking or simply looking for beginner-friendly recipes, there are plenty of options that capture the spirit of this significant Buddhist festival. Here are some simple recipes that anyone can try!

- Vegetable Stir-Fry

Ingredients:- 2 cups mixed vegetables (carrots, bell peppers, broccoli)- 2 tablespoons soy sauce- 1 tablespoon sesame oil- 1 teaspoon ginger, minced- 1 garlic clove, minced- Cooked rice for servingInstructions:1. Heat sesame oil in a pan over medium heat.2. Add garlic and ginger, sautéing until fragrant.3. Toss in mixed vegetables and stir-fry for 5-7 minutes until tender.4. Add soy sauce and mix well.5. Serve over cooked rice.

- Coconut Rice

Ingredients:- 1 cup jasmine rice- 1 cup coconut milk- 1 cup water- 1 tablespoon sugar- A pinch of saltInstructions:1. Rinse the jasmine rice under cold water until the water runs clear.2. In a pot, combine rice, coconut milk, water, sugar, and salt.3. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low and cover.4. Cook for 15-20 minutes or until rice is fluffy.5. Fluff with a fork and serve warm.

- Fresh Fruit Salad

Ingredients:- 1 cup watermelon, cubed- 1 cup pineapple, cubed- 1 cup mango, diced- Juice of 1 lime- Fresh mint leaves for garnishInstructions:1. In a large bowl, combine all the fruit.2. Drizzle with lime juice and toss gently.3. Garnish with fresh mint leaves before serving.

These recipes are not only easy to prepare but also reflect the values of simplicity and mindfulness celebrated during Vesak Day. By using fresh, wholesome ingredients, you create meals that nourish both the body and spirit.

Furthermore, incorporating traditional elements, such as using seasonal vegetables or fresh herbs, can enhance the authenticity of your dishes. For example, adding Thai basil to your stir-fry or using lemongrass in your coconut rice can elevate the flavors and make your meal feel more connected to the cultural roots of the festival.

As you prepare these dishes, remember that cooking is not just about the food; it is also an opportunity to practice mindfulness and gratitude. Take your time, enjoy the process, and reflect on the significance of Vesak Day as you share these meals with family and friends.

In conclusion, these beginner-friendly recipes are a great way to engage with the traditions of Vesak Day while honing your cooking skills. With a little creativity and care, you can create a meaningful and delicious celebration right in your own kitchen.

How Can You Incorporate Traditional Elements into Your Meals?

When celebrating Vesak Day, the importance of food cannot be overstated. It serves as a bridge connecting the past traditions with present practices, allowing individuals to immerse themselves in the rich cultural heritage of Buddhism. Incorporating traditional elements into your Vesak Day meals is not just about following a recipe; it’s about honoring the festival’s deep-rooted significance and fostering a sense of community.

Using fresh herbs and seasonal vegetables in your Vesak Day dishes enhances authenticity and flavor. These ingredients are often locally sourced, reflecting the Buddhist principle of mindfulness and respect for nature. For instance, herbs like basil, cilantro, and mint not only elevate the taste but also symbolize purity and freshness, which align perfectly with the festival’s themes of renewal and enlightenment.

To truly embrace the spirit of Vesak Day, consider sourcing your ingredients from local farmers’ markets or community-supported agriculture (CSA). This approach not only supports local economies but also reduces your carbon footprint, reflecting the Buddhist teaching of interconnectedness. Additionally, choosing organic produce can enhance the overall quality of your meals, allowing you to celebrate in a way that respects the environment.

- Vegetable Stir-Fry: A colorful mix of seasonal vegetables sautéed with fresh herbs makes for a vibrant dish that is both nutritious and delicious.

- Herb-Infused Rice: Cook your rice with a blend of herbs like lemongrass and pandan leaves to add aromatic flavors that elevate the meal.

- Fresh Spring Rolls: Use rice paper to wrap fresh vegetables and herbs, serving them with a tangy dipping sauce that embodies the spirit of sharing.

The presentation of your Vesak Day meals can also reflect traditional elements. Using natural materials for serving dishes, such as bamboo or clay, can enhance the aesthetic appeal and connection to nature. Consider arranging your dishes in a way that reflects the Buddhist concept of harmony, using colors and shapes that are pleasing to the eye.

In many cultures, Vesak Day meals are prepared collectively, highlighting the significance of community and togetherness. Engaging family and friends in the cooking process not only makes it more enjoyable but also reinforces the values of sharing and generosity. This communal aspect can be a beautiful way to connect with others while honoring the teachings of Buddha.

While traditional recipes are essential, adapting them to accommodate various dietary preferences can make your Vesak Day meal more inclusive. For instance, consider offering a vegan version of a popular dish by substituting animal products with plant-based alternatives. This approach not only respects individual choices but also aligns with the Buddhist value of compassion for all living beings.

By thoughtfully incorporating traditional elements such as fresh herbs and seasonal vegetables, you can create meals that resonate with the cultural roots of Vesak Day. This not only enhances the flavor and authenticity of your dishes but also deepens your connection to the festival and its teachings. Celebrating Vesak Day with mindful food choices allows you to honor the past while nurturing the present.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What foods are traditionally eaten on Vesak Day?

On Vesak Day, traditional foods often include a variety of vegetarian dishes such as rice, curries, and fresh fruits. These foods are prepared with mindfulness and are rich in cultural significance, representing purity and gratitude.

- Why is vegetarianism emphasized during Vesak Day?

Vegetarianism is a key practice among Buddhists during Vesak Day as it reflects compassion and respect for all living beings. Embracing a plant-based diet during this celebration aligns with the core values of Buddhism.

- How are Vesak Day dishes prepared?

Dishes for Vesak Day are usually prepared simply, focusing on fresh, local ingredients. This method not only nourishes the body but also embodies the mindfulness and care that are central to Buddhist teachings.

- What desserts are popular during Vesak Day?

Sweet treats like rice cakes and coconut pudding are commonly enjoyed during Vesak Day. These desserts symbolize the sweetness of life and the joy of spiritual renewal that the festival celebrates.

- How do different cultures celebrate Vesak Day with food?

Different cultures have unique culinary traditions for Vesak Day. For example, Thailand features ‘khao tom,’ while Chinese communities enjoy ‘Buddha’s delight,’ showcasing the diverse ways Buddhist communities honor this significant day.

- What is the significance of food offerings during Vesak Day?

Food offerings made during Vesak Day serve as acts of devotion and gratitude. They reinforce the connection between individuals, the community, and the spiritual significance of food in Buddhist practices.

- How can I prepare Vesak Day foods at home?

Preparing Vesak Day foods at home can be a rewarding experience! Simple recipes like vegetable stir-fries and rice dishes are perfect for beginners, allowing everyone to participate meaningfully in the celebration.