Billowing black hair, eyes screaming rage, fangs bared, Kali rushed towards Rakhtabeej with her scimitar and, with one fell swoop, decapitated him. She immediately closed her mouth around the bloodstream emanating from the neck and drank it all in until Rakhtabeej’s veins ran dry.

According to ancient Hindu texts, Kali, meaning “she who is black,” is the Goddess of Death, time, and doomsday. She was born from the combination of the divine energies of all the Gods to defeat the unbeatable demon Raktabeej (meaning Blood-seed). Every time he was attacked, more demons emerged from the blood spilled on the ground.

The Goddess had to cut through legions of demons who had emerged from Rakhtabeej’s blood to reach him and put an end to his tyranny.

Depicted with a long, lolling red tongue, completely naked, wearing a necklace and skirt made of severed heads and arms that cover her nudity, reverence for Kali has dramatically changed in the Indian subcontinent over a hundred years. India Currents is a non-profit newsroom for the Indian American diaspora; if you enjoy our free stories, please lend us your support.

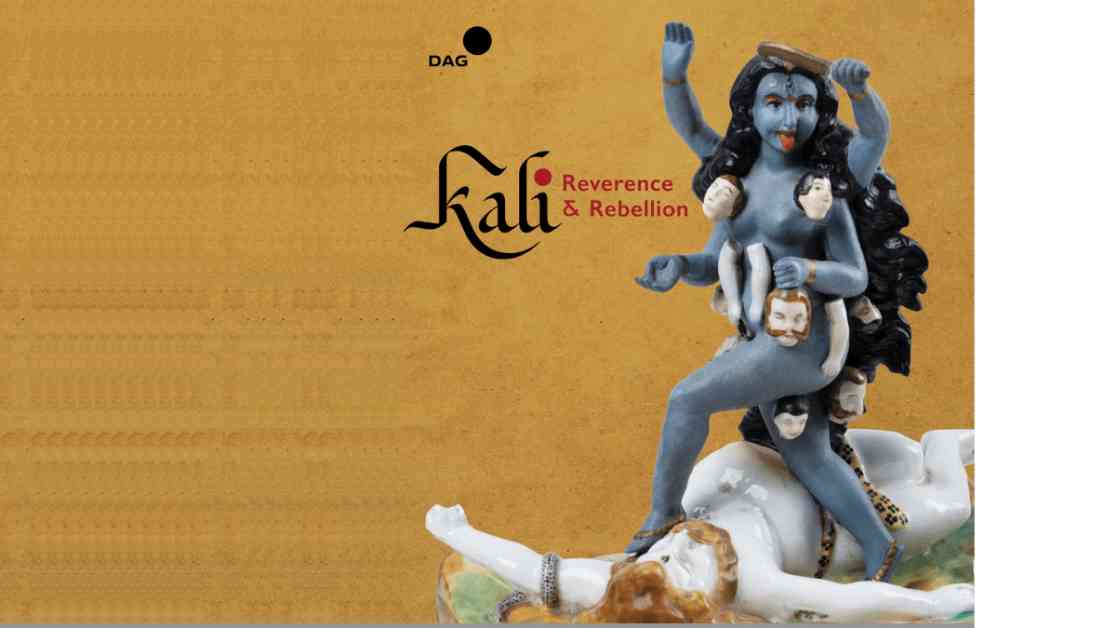

Reverence & Rebellion

An exhibition titled “Kali Reverence and Rebellion” by DAG opened in early February in New Delhi, India. Curated by Gayatri Sinha of the Critical Collective, which works to build knowledge of the arts in India, the exhibition features works by Indians and Europeans spanning centuries—from the 1800s well into the 2000s. It featured artistic depictions of the Goddess in various mediums, such as miniature painting, porcelain, modern lithography, acrylic glass, and illustrations. It traced Kali’s pervasive influence across the subcontinent and explored Kali and her cohorts’ notions of the divine feminine by natives and colonialists alike.

The exhibition can be viewed on the DAG website. After 22 March 2024, it will be moved from ongoing to archive under exhibitions and can be viewed there. Ashish Anand, CEO and MD of DAG, said that the company’s exhibitions and publications program has steadily evolved to emphasize the importance of in-depth academic and curatorial research and execution.

“To make complex ideas and curated exhibitions more accessible to a diverse range of visitors, I aim to contest existing perceptions that separate galleries and museums into distinct categories, at least when it comes to viewership and the dissemination of cultural knowledge. Kali, like other projects in DAG’s recent history, is a proactive step in this direction,” he added.

According to Sinha, “Kali has accumulated a rich history through her transformation over the centuries, commanding a strong hold over the Indian devotional and popular landscape. As a set of abstract principles, Kali stands for death, destruction, rejuvenation, and power.”

“Herein, she makes her way into the work of artists like M. F. Husain, K. C. Pyne, P. T. Reddy, and Nirode Mazumdar, among others, where her ritual iconography is abandoned for the play of the individual artists’ imagination,” she adds.

Early Perceptions and Evolution of the Goddess’ Image

British missionaries and imperialists in India viewed Kali worship as a depraved cult of violence that justified their civilized presence. Symbolizing death, time, and change, Kali was misunderstood as a deity of violence by colonial powers. And that image has persisted well into modern times.

In Temple of Doom, the second installment of the blockbuster Indiana Jones movie franchise, set in colonial-era India, the villain worships the Goddess Kali and engages in sacrificial rituals to chants of “Rise and kill, for the love of Kali.”

One of the striking exhibits depicts a procession of the Goddess, based on an 1840 painting by Russian artist and traveler Prince Aleksandr Mikhailovich Saltuikov (Alexis Soltykoff). The painting depicts the colonial interpretation of Kali—the Thuggee Cult’s terrifying deity. The print showcases a night-time parade where Kali and her alleged army celebrate her presence through music and dance. The idol wears a necklace of skulls, has severed heads in her lower hands, and has a large sickle in her upper right hand.

A symbol of resistance

The Indian independence movement used the British fear of Kali and her followers to make the Goddess a symbol of resistance against colonialism. During India’s nationalist movement, the image of Kali appeared widely in popular culture, especially on posters urging people to join the struggle.

Subhash Chandra Bose, a nationalist freedom fighter, found inspiration in Kali worship. He viewed it as a way to resist and a basis for his moral conduct.

One artwork at the exhibition portrays Bose against the Indian flag with a spinning wheel at its center, using Chhinnamasta’s imagery. In the image, Bose holds his head in one hand and a sword in the other, with blood forming a map of India below. Nearby are the heads of martyrs, symbolizing those who sacrificed their lives for the nation. The artwork carries the inscription “Jai Hind,” a phrase popularized by Bose, visually representing his famous words: “Give me your blood, and I’ll give you freedom.”

Kali has continued to evoke volatile responses in politics and popular culture.

Courting controversy

In 2015, the Goddess’ image was projected onto New York’s Empire State Building to raise awareness about climate change and nature’s power. However, this use of Kali’s image upset many Indians, who found it disrespectful and inappropriate.

In July 2022, Toronto-based filmmaker Leena Manimekalai courted controversy after she tweeted a poster of her documentary Kaali depicting a character from the film dressed as Goddess Kali, smoking a cigarette and holding a trident in one hand and the LGBTQ flag in the other. The poster was heavily criticized, leading to a police complaint against the filmmaker.

Last year, the Ukraine Defence Ministry faced backlash for a controversial depiction of Kali amidst its war with Russia.

Goddess of the Marginalised

Kali has also become a symbol of empowerment for disenfranchised groups as she destroys oppressive norms and unjust power structures. The Goddess’ acceptance transcends social, religious, and gender norms, which is unique.

In the exhibition catalog, Sinha notes that disenfranchised groups, like women and tribals, appropriated Kali over a hundred years, consolidating the goddess’s image as a champion of marginalized communities. The Santal community in colonial Bengal adopted Kali worship during their anti-landlord movement. Although Kali likely had tribal origins, Jitu Santal, the leader of local protests among sharecroppers, learned about Kali worship from a Congress worker.

In 1926, he converted to Hinduism and Kali worship, establishing what he saw as a new religion for his people. Sarkar suggests that Kali, originally a tribal deity, was absorbed into Brahmanical religion but later re-entered the tribal sacred universe, which is ironic. Kali’s significance lies in navigating Brahminical and indigenous religious practices, bridging domestic rituals with mass protests, and challenging established norms.

Gender fluidity

Kali is also celebrated as a symbol of gender fluidity, especially in the social context of the Kali temple in Pavagadh, Gujarat. At this temple, Kalika Mata is worshipped alongside Mahakali and Bahuchara. The LGBTQIA+ community reveres Bahuchara and has a significant following among transgender individuals. In contrast to the fair and beautiful Ambaji Mata worshipped in Banaskantha, Gujarat, these goddesses at the Pavagadh temple represent and even endorse caste and gender fluidity.

In recent decades, says Sinha, especially since the 1980s, Kali has been reevaluated, led by academics, feminists from India and the West, and those interested in Subaltern Studies. As Indian feminists protested women’s issues in cities during the 1980s, Kali became a symbol of women’s issues for them.

According to them, Kali was initially seen as a complex goddess representing all aspects of existence. However, over time, patriarchy reduced her image to that of a fragmented, dark, and dangerous goddess. This degradation was intentional. Therefore, feminists argue that Kali’s complexity needs to be reassessed and her original significance restored.

Sinha says that though the goddess has primarily served the religious, community, and caste-related needs, her worship reflects various social concerns. “For instance, in Lakhna town in Uttar Pradesh’s Etawah district, there stands a 200-year-old Kali temple, where only Dalits are priests. Within the temple complex, there also exists a mazar (mausoleum) for the Sufi saint, Sayyid Baba,” she adds.

What Sets Kali Apart

Kali’s dark complexion sets her apart from other Hindu goddesses.

Modern idols of Kali depict her in a benign form. She looks tame and benevolent and appears to playfully stick her tongue out – a far cry from the rage that decimated Rakhtabeej. But in her original form, the Goddess does not negotiate forgiveness or the execution of punishment; she is uncompromising in war.

Unlike Durga, who swiftly aids her devotees, Kali constantly reminds them of life’s darker aspects. One must be brave to face Kali, who embodies life and death. But understanding her illuminates our inner tranquility.

Kali is a goddess who embodies wild and unrestrained nature beyond societal norms. She is a symbol of feminine strength, embraced by different communities. She restores order and reflects the uncompromising nature of justice. Hindus see Kali as a reminder of life’s unpredictable and irrepressible elements.

She represents the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death.

“What is Kali’s truth? She is the prime example of untamable, resistant feminine power, unvanquished, solitary and proud, to be claimed by various groups and communities,” notes Sinha.