This article delves into the feasibility of filing a lawsuit without legal representation in the United States. It examines the processes involved, the challenges faced, and provides tips for effective self-representation.

Understanding Pro Se Representation

Pro se representation is a term used when individuals choose to represent themselves in legal proceedings. In the U.S. court system, this is a legal right, allowing individuals to navigate their cases without the assistance of an attorney. However, it is essential to understand that while self-representation is permitted, it comes with significant responsibilities and potential pitfalls.

Types of Cases You Can Handle Alone

- Small Claims Court: This venue is specifically designed for individuals to resolve disputes involving smaller amounts of money, typically without the need for legal counsel.

- Civil Matters: Certain civil cases, such as landlord-tenant disputes and minor contract issues, can also be managed by individuals without legal representation.

Small Claims Court

Small claims court is an excellent option for those seeking to resolve disputes quickly and cost-effectively. The processes involved are generally straightforward, allowing individuals to present their cases directly to a judge.

Filing Procedures

To initiate a small claims lawsuit, individuals must follow specific steps:

- Determine the appropriate court.

- Complete the necessary forms.

- File the forms and pay the required fees.

- Serve the defendant with the court papers.

Limitations and Considerations

While small claims courts offer an accessible route for self-representation, there are limitations. Each state has its own maximum claim amounts, and certain types of cases, such as divorce or personal injury claims, are typically excluded from small claims court.

Challenges of Filing Without a Lawyer

Self-representation presents various challenges:

- Legal Knowledge and Procedures: A lack of understanding of legal terminology and procedural rules can significantly hinder one’s ability to effectively present a case.

- Emotional and Psychological Factors: The stress of navigating a lawsuit can be overwhelming, leading to anxiety and emotional strain.

Resources for Self-Represented Litigants

Fortunately, numerous resources are available for individuals filing lawsuits without an attorney:

- Online Legal Resources: Websites such as Nolo and LegalZoom offer valuable information and tools for self-represented litigants.

- Court Self-Help Centers: Many courts provide self-help centers that offer guidance on filling out forms and understanding procedures.

Tips for Successfully Representing Yourself

To enhance your chances of success in self-representation, consider the following tips:

- Thorough Research: Understanding case law and legal precedents relevant to your situation is crucial.

- Organizing Your Case: Keep all documents and evidence well-organized to present a clear and compelling argument.

When to Consider Hiring a Lawyer

While self-representation is possible, certain circumstances may warrant hiring an attorney:

- Complex Legal Issues: If your case involves intricate legal matters, professional expertise may be necessary.

- Emotional Stress and Burnout: If the emotional toll of self-representation becomes overwhelming, seeking legal assistance can provide relief.

In conclusion, while filing a lawsuit without legal representation is possible in the U.S., it requires careful consideration, thorough preparation, and an understanding of the legal landscape. By leveraging available resources and implementing effective strategies, individuals can navigate the complexities of the legal system more confidently.

Understanding Pro Se Representation

is a critical aspect of navigating the U.S. legal system. Pro se representation allows individuals to represent themselves in court without a lawyer. While this option can be empowering, it also comes with significant responsibilities and challenges. This section delves into the legal basis of self-representation, its implications, and essential considerations for those choosing this path.

In the United States, the right to represent oneself in legal matters is rooted in the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the right to counsel but also implies the right to forgo legal representation. This principle is further supported by various court rulings, affirming that individuals have the autonomy to manage their own legal affairs. However, it is crucial to understand that self-representation is not a right without limitations. Courts expect pro se litigants to adhere to the same rules and procedures as licensed attorneys, which can be daunting for those unfamiliar with legal processes.

When considering pro se representation, individuals should be aware of the types of cases that are more manageable without a lawyer. Commonly, small claims court is designed for self-representation, allowing individuals to resolve disputes involving limited monetary amounts without the need for legal counsel. Other civil matters, such as landlord-tenant disputes or minor contract issues, may also be suitable for self-representation.

However, navigating the legal system without an attorney poses several challenges. One significant hurdle is the lack of legal knowledge. Many pro se litigants struggle with understanding legal terminology, procedural rules, and court protocols, which can lead to mistakes that jeopardize their cases. Emotional and psychological factors also play a role, as the stress of managing a case alone can be overwhelming. Individuals must be prepared for the emotional toll that legal proceedings can take, and they should consider their mental resilience when opting for self-representation.

To support those choosing the pro se route, numerous resources are available. Many courts offer self-help centers that provide guidance on filing procedures, necessary forms, and general legal information. Additionally, online legal resources can be invaluable, with websites dedicated to helping individuals understand their rights and the intricacies of the legal process.

For those considering pro se representation, it is essential to conduct thorough research. Understanding case law and relevant legal precedents can significantly impact the outcome of a case. Moreover, organizing case materials, such as documents and evidence, can streamline the self-representation process and enhance the likelihood of a favorable outcome.

While self-representation is an option, it is not always the best choice. Individuals facing complex legal issues or those experiencing significant emotional stress may benefit from consulting a lawyer. Recognizing when to seek professional assistance is crucial, as certain scenarios may require the expertise of an attorney to navigate effectively.

In summary, pro se representation is a viable option for many individuals in the U.S. legal system, offering the opportunity to advocate for oneself. However, it comes with inherent challenges that require careful consideration and preparation. By understanding the legal basis for self-representation, recognizing the types of cases suitable for this approach, and utilizing available resources, individuals can better navigate the complexities of representing themselves in court.

Types of Cases You Can Handle Alone

When considering whether to represent yourself in legal matters, it’s essential to understand that not all cases are suitable for self-representation. However, certain types of cases can be effectively managed without the assistance of a lawyer. In this section, we will explore the various categories of cases that individuals may handle alone, including small claims, landlord-tenant disputes, and other civil matters.

Small claims courts are designed for individuals to resolve disputes involving relatively low amounts of money without needing legal representation. These courts typically handle cases where the claim amount is under a specific threshold, which varies by state. For example, in many jurisdictions, the limit is often set between $2,500 and $10,000.

- Common Types of Small Claims:

- Unpaid debts

- Property damage

- Contract disputes

To initiate a small claims lawsuit, you typically need to follow these steps:

- Determine the appropriate court based on the amount and type of claim.

- Complete the necessary forms, which can often be found online or at the courthouse.

- File the forms and pay the required filing fee.

- Serve the defendant with a copy of the claim.

While small claims court is accessible, there are limitations to keep in mind:

- Claim Amounts: Ensure your claim does not exceed the court’s limit.

- Types of Cases Excluded: Some cases, such as those involving divorce or child custody, are not suitable for small claims court.

In addition to small claims, certain civil cases can be handled without a lawyer. Common examples include:

- Landlord-Tenant Disputes: Issues such as eviction proceedings or security deposit disputes can often be resolved in small claims court.

- Consumer Complaints: Cases involving faulty products or services can also be pursued without legal representation.

While self-representation in these cases is feasible, it’s crucial to be aware of the potential risks:

- Legal Knowledge: A lack of understanding of legal processes and terminology can hinder your case.

- Procedural Errors: Mistakes in filing or presenting your case can lead to unfavorable outcomes.

In summary, while many individuals can successfully manage small claims and certain civil matters without a lawyer, it is essential to be informed about the processes, limitations, and potential risks involved. Adequate preparation and research can significantly enhance your chances of a favorable outcome when representing yourself in these types of cases.

Small Claims Court

The serves as a vital mechanism for individuals seeking to resolve disputes without the need for legal representation. This court is designed to handle minor civil disputes, making it accessible for those who may not have the resources to hire an attorney. Understanding the processes and limits associated with small claims cases is essential for anyone considering this option.

What Types of Cases Can Be Filed?

Small claims courts typically handle cases involving monetary disputes that fall below a certain threshold, which varies by state. Common types of cases include:

- Contract disputes

- Property damage claims

- Landlord-tenant disputes

- Consumer complaints

- Personal injury claims

Filing Procedures

Initiating a small claims lawsuit involves several steps:

- Determine Jurisdiction: Ensure that your case qualifies for small claims court within your jurisdiction.

- File Your Claim: Complete the necessary forms, providing details about the dispute and the amount you are seeking.

- Pay Filing Fees: Submit your claim along with the required filing fee, which varies by location.

- Serve the Defendant: Notify the other party of the claim through proper legal channels.

- Prepare for Court: Gather evidence, including documents and witness statements, to support your case.

Limits and Considerations

While small claims court is designed to be user-friendly, there are important limitations to consider:

- Monetary Limits: Each state imposes a cap on the amount you can claim, often ranging from $2,500 to $25,000.

- Types of Cases Excluded: Certain cases, such as those involving divorce, child custody, or defamation, are typically not permitted in small claims court.

Advantages of Small Claims Court

Filing in small claims court offers several advantages:

- Simplified Process: The procedures are straightforward, allowing individuals to represent themselves without extensive legal knowledge.

- Cost-Effective: Filing fees are generally low, and there are no attorney fees involved.

- Quick Resolution: Cases are often resolved more rapidly than in traditional courts, with many hearings taking place within a few months.

Challenges in Small Claims Court

Despite its advantages, self-representation in small claims court can present challenges:

- Understanding Legal Procedures: Navigating court procedures can be daunting, and a lack of familiarity may hinder your case.

- Emotional Stress: Representing oneself can be emotionally taxing, especially when facing a dispute with a party you know.

Conclusion

Small claims court provides an accessible avenue for individuals to resolve disputes independently. By understanding the processes, limits, and challenges associated with small claims cases, individuals can better prepare themselves for their court appearance and increase their chances of a favorable outcome.

Filing Procedures

in small claims court can initially seem daunting, but understanding the necessary steps can streamline the process significantly. This section provides a comprehensive overview of how to effectively initiate a small claims lawsuit.

First and foremost, it is essential to determine your eligibility for small claims court. Typically, these courts handle disputes involving limited monetary amounts, which can vary by state. For instance, many states cap claims at $5,000 to $10,000. Be sure to check your local court’s guidelines for specific limits.

Once you establish that your case qualifies, the next step is to gather necessary documentation. This includes any evidence that supports your claim, such as contracts, receipts, photographs, or witness statements. Organizing these documents will not only help in presenting your case but also ensure you have everything you need when filing.

- Step 1: Complete the necessary forms. Most small claims courts provide standardized forms to initiate a lawsuit. These forms typically require basic information about the parties involved and the nature of the claim.

- Step 2: File your claim. Submit your completed forms to the court clerk, along with the required filing fee. The fee can vary, so check with your local court for exact amounts.

- Step 3: Serve the defendant. After filing, you must notify the other party (the defendant) about the lawsuit. This process, known as “service of process,” can typically be done through certified mail or by hiring a process server.

- Step 4: Prepare for the hearing. Familiarize yourself with court procedures and prepare your arguments. Practice presenting your case clearly and concisely, as you will have a limited amount of time to speak during the hearing.

It is also crucial to be aware of any deadlines associated with your case. Each state has specific timelines for filing claims and serving documents, and missing these deadlines can result in your case being dismissed.

Additionally, consider the possibility of settling out of court. Many disputes can be resolved through negotiation, which can save time and money for both parties. If a settlement is reached, ensure that it is documented in writing to avoid future disputes.

Finally, prepare for the hearing day. Arrive early, dress appropriately, and bring all necessary documents and evidence. During the hearing, present your case clearly, listen to the defendant’s arguments, and be respectful to the judge and all parties involved.

By following these structured steps, you can navigate the small claims court process more effectively, increasing your chances of a favorable outcome. Remember, while self-representation is an option, understanding the legal process is key to successfully advocating for your rights.

Limitations and Considerations

When considering small claims court as an option for resolving disputes, it is important to understand the inherent limitations and considerations associated with this legal avenue. While small claims courts are designed to be accessible for individuals representing themselves, they come with specific restrictions that can impact the type of cases that can be filed and the amount of money that can be claimed.

One of the primary limitations of small claims court is the maximum claim amount. Each state in the U.S. sets its own cap on the amount that can be claimed in small claims court, which typically ranges from $2,500 to $25,000. For example, states like California allow claims up to $10,000 for individuals, while New York has a limit of $5,000. It is crucial for potential litigants to verify their state’s maximum claim amount before proceeding, as exceeding this limit will necessitate pursuing the case in a higher court, which may require legal representation.

In addition to claim limits, there are also types of cases that are typically excluded from small claims court. These exclusions can vary by state but generally include:

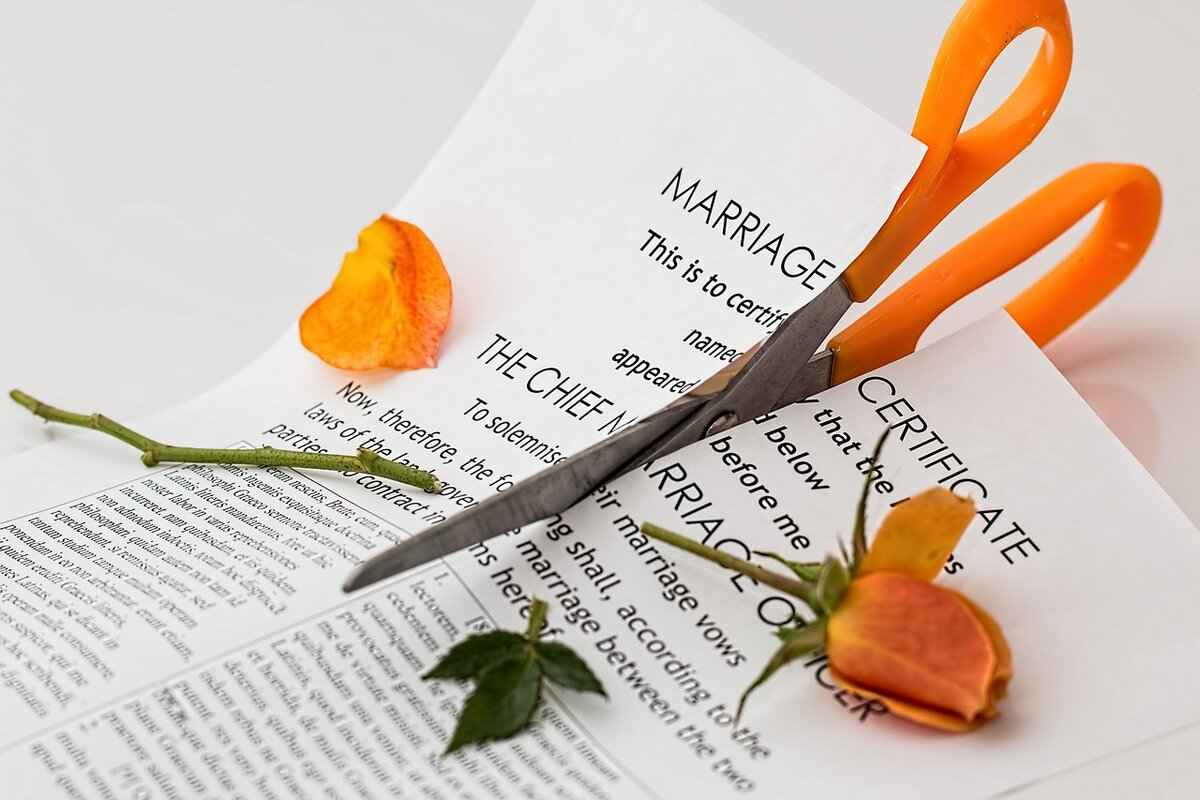

- Cases involving divorce or child custody

- Personal injury claims exceeding the monetary limit

- Defamation cases

- Claims against governmental entities or public officials

- Class action lawsuits

Understanding these exclusions is essential, as attempting to file a case that does not qualify for small claims court can result in wasted time and resources. Additionally, small claims courts do not handle appeals in the same manner as higher courts; generally, the decisions made by small claims judges are final, and there is limited opportunity for appeal except under specific circumstances.

Another consideration is the legal procedures involved in small claims court. While the process is designed to be straightforward, individuals must still adhere to certain rules and procedures, such as properly notifying the defendant of the claim and preparing necessary documentation. Failure to follow these procedures can lead to dismissal of the case.

It is also worth noting that while small claims courts strive to be user-friendly, the absence of legal representation can pose challenges. Individuals may lack the knowledge of legal terminology and procedural rules, potentially hindering their ability to present their case effectively. This is particularly true in more complex cases or when the opposing party is represented by an attorney.

In summary, while small claims court offers a valuable option for resolving disputes without the need for a lawyer, it is essential to be aware of the limitations regarding claim amounts and case types. By understanding these factors, individuals can make informed decisions about whether to pursue their claims in small claims court or seek alternative legal avenues.

Civil Cases

encompass a wide range of legal disputes, and in certain situations, individuals may choose to represent themselves, known as pro se representation. Among these cases, landlord-tenant disputes are common scenarios where self-representation is often permitted. This section delves into the intricacies of navigating civil matters without an attorney, providing insights and guidance for those considering this route.

Understanding the nuances of civil cases is essential for individuals who opt for self-representation. Landlord-tenant disputes typically arise from issues such as non-payment of rent, lease violations, or eviction proceedings. These cases are often heard in housing courts, which are designed to address such matters efficiently. The procedures in these courts can vary significantly from those in other civil courts, making it crucial for self-represented litigants to familiarize themselves with specific rules and regulations.

- Filing a Complaint: The first step in a landlord-tenant dispute is filing a complaint. This document outlines the issues at hand and the relief sought. It must be submitted to the appropriate court, along with any required fees.

- Gathering Evidence: Evidence is vital in civil cases. Self-represented litigants should collect documents such as lease agreements, payment records, and correspondence with the landlord or tenant to support their claims.

- Understanding Court Procedures: Each court has its own procedures. Familiarizing oneself with these rules, including timelines for filing documents and deadlines for responses, is crucial for a successful outcome.

While self-representation is feasible, it presents unique challenges. A significant hurdle is the legal knowledge required to navigate the complexities of civil law. Many individuals may find themselves overwhelmed by legal terminology and procedural intricacies. It is advisable to conduct thorough research or seek guidance from resources available to pro se litigants.

| Challenges of Self-Representation | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Lack of Legal Knowledge | Utilize online legal resources and court self-help centers. |

| Emotional Stress | Consider joining support groups or seeking counseling. |

| Organizing Case Materials | Develop a systematic approach to document management. |

In addition to understanding the legal framework, self-represented litigants should also prepare for the emotional aspects of handling a civil case. The stress and anxiety associated with navigating the legal system can be significant. It is essential to maintain a level head and seek support from friends, family, or community resources. Engaging in stress-relief activities, such as exercise or meditation, can also be beneficial.

For those who find the prospect of self-representation daunting, it is important to recognize when to seek professional legal assistance. If the case involves complex legal issues or if the emotional burden becomes overwhelming, consulting with an attorney may be the best course of action. Legal professionals can provide valuable insights and representation, ensuring that the individual’s rights are protected throughout the process.

In summary, while self-representation in civil cases like landlord-tenant disputes is possible, it requires careful preparation, a solid understanding of the legal system, and awareness of the challenges involved. By leveraging available resources and staying organized, individuals can navigate their cases more effectively, potentially achieving favorable outcomes without the need for an attorney.

Challenges of Filing Without a Lawyer

Filing a lawsuit without a lawyer can be a daunting task, and many individuals may find themselves overwhelmed by the intricacies of the legal system. The challenges of self-representation are multifaceted, and understanding these obstacles is crucial for anyone considering this path.

- Lack of Legal Knowledge: One of the most significant hurdles is the absence of legal expertise. Understanding legal terminology, procedures, and the nuances of the law is essential for effectively navigating the court system. Many self-represented litigants struggle with complex legal concepts, which can lead to mistakes that jeopardize their cases.

- Procedural Missteps: The legal system is filled with specific rules and procedures that must be followed meticulously. Missing a deadline, filing incorrect documents, or failing to adhere to court protocols can result in dismissal of the case. Self-represented litigants often lack the guidance to avoid these pitfalls.

- Emotional Strain: The process of filing a lawsuit can be emotionally taxing. Individuals may experience stress, anxiety, and frustration as they navigate their cases. The emotional burden can cloud judgment, leading to poor decision-making and further complicating the legal process.

- Limited Resources: Many self-represented litigants do not have access to the same resources as attorneys. This includes legal research tools, professional networks, and support systems that can provide critical guidance and assistance. The lack of these resources can hinder their ability to present a compelling case.

- Difficulty in Presenting Evidence: Effectively presenting evidence in court is vital for the success of any case. Self-represented litigants may struggle with understanding what constitutes admissible evidence and how to properly present it. This can weaken their arguments and diminish their chances of a favorable outcome.

The emotional toll of self-representation cannot be underestimated. Individuals may feel isolated, particularly when they lack a support system or professional guidance. This isolation can lead to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt, further complicating the process. Additionally, the fear of the unknown can exacerbate anxiety levels, making it challenging to focus on the legal aspects of the case.

- Educate Yourself: Taking the time to learn about the legal process and relevant laws can empower self-represented litigants. Numerous online resources, including legal websites and forums, provide valuable information that can help demystify the legal system.

- Organize Your Case: Maintaining organized documentation is critical. Creating a system for managing evidence, filings, and deadlines can reduce stress and improve the chances of success. Consider using spreadsheets or project management tools to keep everything in order.

- Seek Support: Many courts offer self-help centers and resources for individuals representing themselves. Utilizing these services can provide guidance and support, helping to navigate the complexities of legal proceedings.

- Consider Mediation: In certain cases, mediation can be a more manageable alternative to court. This process involves a neutral third party who helps facilitate a resolution, often reducing the emotional strain associated with litigation.

In summary, while self-representation can be a viable option for some, it is fraught with challenges that require careful consideration and preparation. By understanding these obstacles and employing effective strategies, individuals can better navigate the legal landscape and advocate for their rights.

Legal Knowledge and Procedures

When individuals choose to represent themselves in legal matters, they often encounter significant challenges due to a lack of legal knowledge and unfamiliarity with procedural rules. Understanding legal terminology and the nuances of court procedures is essential for anyone considering self-representation.

Legal terminology can be complex and intimidating. Terms like plaintiff, defendant, jurisdiction, and discovery are just a few examples of the language that legal professionals use regularly. Without a solid grasp of these terms, self-represented litigants may struggle to communicate effectively in court. This can lead to misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and ultimately, unfavorable outcomes in their cases.

Moreover, each court has its own set of procedural rules that govern how cases are filed, how evidence is presented, and how hearings are conducted. These rules can vary widely from one jurisdiction to another. For instance, the process for filing a small claims case is often different from that of a civil lawsuit. A self-represented litigant who fails to follow these rules may find their case dismissed or delayed, which can be both frustrating and costly.

Understanding the specific filing procedures for a given court is crucial. For example, many courts require specific forms to be filled out in a particular way, often accompanied by filing fees. Failing to adhere to these requirements can result in a case being thrown out before it even begins. Furthermore, deadlines for filing motions or submitting evidence are strictly enforced, and missing these deadlines can severely impact a litigant’s chances of success.

In addition to learning about legal terms and procedures, self-represented individuals must also familiarize themselves with the general structure of a court case. This includes knowing how to present their case, what evidence is admissible, and how to question witnesses. For many, this can be an overwhelming task, particularly when they are also dealing with the emotional aspects of their legal situation.

To navigate these challenges effectively, self-represented litigants should consider utilizing available resources. Many courts offer self-help centers where individuals can receive guidance on how to properly fill out forms and understand court procedures. Additionally, online legal resources provide valuable information and templates that can aid in understanding legal concepts and preparing for court.

Furthermore, engaging in thorough research is critical. Self-represented litigants should take the time to learn about their specific legal issue, relevant laws, and any precedents that may apply to their case. This knowledge can empower them to argue their case more effectively and anticipate potential challenges from the opposing party.

In conclusion, while self-representation is a viable option for many individuals, it comes with significant challenges that can be mitigated through a strong understanding of legal terminology and procedural rules. By investing time in education, utilizing available resources, and conducting thorough research, self-represented litigants can enhance their chances of achieving a favorable outcome in their legal matters.

Emotional and Psychological Factors

Filing a lawsuit can be a daunting experience, and the emotional and psychological factors involved in the self-representation process can significantly impact an individual’s journey through the legal system. This section delves into the various psychological challenges that individuals may face when navigating their cases without the assistance of a lawyer.

One of the primary emotional challenges is the stress associated with the legal process. The uncertainty of the outcome, coupled with the complexity of legal language and procedures, can lead to feelings of anxiety. Many individuals find themselves overwhelmed by the requirements of filing paperwork, meeting deadlines, and preparing for hearings. This stress can manifest physically and emotionally, affecting overall well-being.

Another significant factor is the fear of failure. Individuals representing themselves often grapple with self-doubt regarding their ability to effectively present their case. This fear can be exacerbated by a lack of legal knowledge, leading to feelings of inadequacy. Many self-represented litigants worry about making mistakes that could jeopardize their case, which can create a paralyzing sense of pressure.

Moreover, the isolation that comes with self-representation can compound emotional challenges. Unlike those who have legal representation, self-represented litigants may feel alone in their struggles, lacking the support and guidance that an attorney can provide. This sense of isolation can lead to feelings of loneliness and despair, making it more difficult to navigate the legal system effectively.

To combat these emotional hurdles, it is essential for individuals to develop coping strategies. Engaging in stress-reduction techniques such as meditation, exercise, or seeking support from friends and family can help mitigate the emotional toll of self-representation. Additionally, joining support groups for self-represented litigants can provide a sense of community and shared experience, helping individuals feel less isolated.

Furthermore, education plays a crucial role in alleviating anxiety and building confidence. By taking the time to understand legal terminology, procedures, and the specific requirements of their case, individuals can empower themselves and reduce feelings of uncertainty. Many courts offer resources and workshops designed to educate self-represented litigants, which can be invaluable in building knowledge and confidence.

In conclusion, while the emotional and psychological factors associated with self-representation can be challenging, individuals can take proactive steps to manage their stress and build resilience. By seeking support, educating themselves, and developing coping strategies, self-represented litigants can navigate the complexities of the legal system with greater confidence and emotional stability.

Resources for Self-Represented Litigants

Filing a lawsuit without an attorney can be a daunting process, but there are numerous resources available to assist individuals navigating the legal system on their own. Understanding where to find support and guidance is essential for self-represented litigants. Below are some valuable resources that can help you effectively manage your case.

- Online Legal Resources

- There are many reputable websites dedicated to providing legal information and resources. Websites such as Nolo and LegalZoom offer easy-to-understand articles, legal forms, and guides that can help you understand the legal process and your rights.

- Additionally, many state bar associations provide online resources tailored to self-represented litigants, including legal guides and FAQs about filing procedures.

- Court Self-Help Centers

- Many courts across the United States have established self-help centers specifically designed to assist pro se litigants. These centers typically offer free resources such as:

- Workshops on how to file a lawsuit

- Access to legal forms and instructions

- One-on-one assistance from trained staff who can help clarify legal procedures

- To find a self-help center near you, visit your local court’s website or contact the court clerk’s office for more information.

- Legal Aid Organizations

- Non-profit legal aid organizations provide free or low-cost legal assistance to individuals who qualify based on income. These organizations often offer resources for self-represented litigants, including:

- Legal advice and consultations

- Workshops and seminars on various legal topics

- Access to community resources and referrals to attorneys if needed

- To locate a legal aid organization in your area, visit the Legal Services Corporation website.

- Legal Clinics

- Many law schools and community organizations host free legal clinics where individuals can receive advice from law students under the supervision of licensed attorneys. These clinics often focus on specific areas of law, such as family law, housing, or consumer rights, and can be a valuable resource for self-represented litigants.

- Check with local law schools or community centers to find out about upcoming clinics in your area.

- Books and Guides

- Numerous books and guides are available that provide step-by-step instructions for self-representation. Titles such as “Represent Yourself in Court” or “The Complete Guide to Small Claims Court” can offer practical insights and detailed information about the legal process.

- These resources can often be found at local libraries or purchased online.

By utilizing these resources, self-represented litigants can enhance their understanding of the legal process and improve their chances of a successful outcome. Remember, while self-representation is a viable option for many, it is essential to assess your situation carefully and seek professional legal advice when necessary.

Online Legal Resources

The digital age has transformed the way individuals access information, including legal resources. For self-represented litigants, the internet is an invaluable tool, offering a plethora of resources that can assist in navigating the legal landscape. This section delves into some of the most reputable websites and online tools available to those who choose to represent themselves in legal matters.

- Legal Information Websites: Various websites provide comprehensive legal information tailored to the needs of self-represented litigants. Websites like Nolo and FindLaw offer articles, guides, and legal forms that cover a wide range of topics, from family law to civil rights. These platforms are designed to empower individuals with knowledge, helping them understand their rights and responsibilities.

- Online Legal Aid Services: Organizations such as Legal Services Corporation and LawHelp.org provide access to free or low-cost legal assistance. These services can connect self-represented litigants with local resources, offering guidance on how to proceed with their cases effectively.

- Case Law Research Tools: Websites like Justia and LexisNexis allow users to research case law and legal precedents. Understanding relevant case law is crucial for self-represented litigants, as it can inform legal strategies and enhance arguments in court.

- Document Preparation Services: Online platforms such as Rocket Lawyer and LegalZoom offer services for creating legal documents. These sites often provide templates for various legal forms, ensuring that users can file the necessary paperwork accurately and efficiently.

- Legal Forums and Community Support: Online forums like Avvo allow individuals to ask legal questions and receive answers from licensed attorneys. Engaging with a community of individuals facing similar challenges can provide emotional support and practical advice.

In addition to these resources, many state and local courts have developed their own online portals, providing access to court forms, filing procedures, and self-help guides. These portals are tailored to the specific rules and regulations of the jurisdiction, making them essential for anyone looking to file a lawsuit without legal representation.

It is important for self-represented litigants to approach online resources critically. While the internet is filled with valuable information, it is also home to misinformation. Always verify the credibility of the sources and ensure that the information is up-to-date and relevant to your specific legal situation.

By leveraging these online legal resources, self-represented litigants can enhance their understanding of the legal process, prepare more effectively for their cases, and ultimately improve their chances of achieving favorable outcomes.

Court Self-Help Centers

play a vital role in supporting pro se litigants—individuals who choose to represent themselves in legal matters. These centers are designed to provide essential resources, guidance, and assistance to those navigating the complexities of the legal system without the aid of an attorney.

Many courts across the United States have established self-help centers that offer a variety of services tailored to the needs of self-represented litigants. The primary goal of these centers is to empower individuals by equipping them with the necessary tools and knowledge to effectively handle their legal issues.

| Services Offered | Description |

|---|---|

| Legal Information | Self-help centers provide general legal information on a wide range of topics, including family law, small claims, and landlord-tenant disputes. They help individuals understand the legal processes involved in their cases. |

| Forms Assistance | Many centers offer assistance in completing legal forms. Staff members can guide litigants on how to fill out necessary documents accurately to avoid delays or rejections. |

| Workshops and Clinics | Self-help centers often host workshops that cover various legal topics. These sessions provide valuable insights into the court process and tips for effective self-representation. |

| Referral Services | If a case requires legal expertise beyond what a self-help center can provide, they may offer referral services to local attorneys or legal aid organizations. |

Accessing these resources is typically straightforward. Most self-help centers are located within or near courthouses, making them easily accessible to the public. To find a self-help center, individuals can:

- Visit the official website of their local court, where they can find information on available resources.

- Contact the court clerk’s office directly to inquire about the existence and location of nearby self-help centers.

- Utilize online directories that list self-help resources available in various jurisdictions.

It is important to note that while self-help centers provide valuable information and support, they do not offer legal advice. Staff members are typically trained to assist with procedural questions and help individuals understand their rights and responsibilities. Therefore, if a litigant has specific legal questions or needs tailored advice, consulting with a qualified attorney is advisable.

In conclusion, serve as an essential resource for pro se litigants, offering a variety of services designed to facilitate self-representation. By understanding how to access and utilize these resources, individuals can navigate the legal system more effectively, increasing their chances of achieving a favorable outcome in their cases.

Tips for Successfully Representing Yourself

Success in self-representation requires careful planning and preparation. Navigating the legal system without an attorney can be daunting, but with the right strategies, you can significantly enhance your chances of achieving a favorable outcome. This section offers practical tips to help you effectively represent yourself in court.

- Understand the Legal Process: Familiarize yourself with the legal procedures relevant to your case. Each court has its own rules and regulations, so it is essential to understand what is expected of you. This includes knowing how to file documents, deadlines for submissions, and the specific forms required.

- Conduct Thorough Research: Research is critical. Utilize online legal resources, case law databases, and law libraries to gather information pertinent to your case. Understand the laws, regulations, and precedents that apply to your situation. This knowledge will empower you to make informed decisions and present a compelling argument.

- Organize Your Case: Keep your documents and evidence well-organized. Create a binder or digital folder that contains all relevant paperwork, including pleadings, evidence, and correspondence. Use tabs or labels for easy navigation. Proper organization helps you present your case clearly and efficiently.

- Practice Your Presentation: Before your court appearance, practice what you plan to say. Rehearse your arguments, responses to potential questions, and any statements you need to make. This preparation will help you feel more confident and articulate when speaking in front of a judge.

- Stay Professional and Respectful: In court, maintain a professional demeanor. Address the judge and opposing parties respectfully. Avoid emotional outbursts or confrontational behavior, as this can negatively impact your case.

- Seek Feedback: If possible, consult with individuals who have experience in legal matters. They can provide valuable feedback on your case and presentation style. Consider reaching out to legal aid organizations or self-help centers for additional support.

- Be Prepared for the Unexpected: Court proceedings can be unpredictable. Be ready to adapt to changes and respond to unexpected developments. Flexibility and a calm demeanor will serve you well in these situations.

- Utilize Court Resources: Many courts offer resources for self-represented litigants, including self-help centers and legal clinics. Take advantage of these services to gain insights and assistance tailored to your case.

By implementing these strategies, you can improve your self-representation experience and increase your chances of success. Remember, while representing yourself is entirely possible, it requires dedication, preparation, and a willingness to learn. Equip yourself with the necessary tools and knowledge, and approach your case with confidence.

Thorough Research

When navigating the complexities of the legal system without professional representation, conducting thorough research becomes a vital component for self-represented litigants. Understanding the law, relevant case precedents, and procedural rules is essential to effectively advocate for oneself in court.

For individuals considering self-representation, it is crucial to grasp the importance of legal research. This entails not only familiarizing oneself with the laws applicable to their specific case but also understanding how those laws have been interpreted in past rulings. Case law provides insights into how judges have resolved similar issues, which can significantly influence the outcome of a current case.

Moreover, legal precedents establish a framework that courts often follow. Knowledge of these precedents can empower litigants to build stronger arguments. For instance, if a previous court decision supports your position, citing that case can lend credibility to your claims. This not only enhances your argument but also demonstrates to the court that you have done your homework.

To begin the research process, self-represented litigants should consider the following steps:

- Identify Relevant Laws: Start by pinpointing the statutes and regulations that apply to your case. This can usually be done through state or federal legal databases.

- Review Case Law: Utilize legal research platforms such as Westlaw or LexisNexis to find cases that pertain to your situation. Pay attention to the facts of the cases, the legal issues addressed, and the court’s reasoning.

- Understand Court Procedures: Each court has its own set of rules and procedures. Familiarizing yourself with these can prevent procedural missteps that might jeopardize your case.

Additionally, legal terminology can be daunting for those unfamiliar with it. Taking the time to understand key legal terms and phrases can aid in comprehending court documents and communications. Various online resources and legal dictionaries can assist with this aspect of research.

Furthermore, organizing your findings is equally important. Keeping detailed notes on relevant cases, statutes, and procedural rules can streamline the preparation process. Consider creating a binder or digital file that categorizes your research for easy access during court appearances.

In the age of technology, many online resources are available to assist self-represented litigants. Websites such as the Legal Information Institute (LII) and state court websites often provide valuable resources, including guides on legal procedures, sample forms, and even links to legal aid organizations that can offer assistance.

Finally, while thorough research is crucial, it is also important to recognize when the complexities of a case may warrant professional legal assistance. If the legal issues become too intricate or if the emotional toll becomes overwhelming, seeking the help of an attorney can be a wise decision.

In conclusion, conducting thorough research lays the foundation for effective self-representation. By understanding relevant laws, reviewing case precedents, and familiarizing oneself with court procedures, self-represented litigants can significantly enhance their chances of achieving a favorable outcome.

Organizing Your Case

When navigating the legal system without an attorney, effective organization of your case is paramount. This process not only aids in presenting your argument clearly but also enhances your confidence in managing your legal matters. Below are several strategies to help you organize your documents and evidence effectively.

- Create a Case File: Start by establishing a dedicated case file. This file should include all relevant documents, such as pleadings, correspondence, and evidence. Organizing these materials in one place will save you time and reduce stress.

- Use Dividers and Labels: Within your case file, utilize dividers and labels to categorize documents. Sections might include evidence, correspondence, court documents, and notes. This method allows for quick access to necessary information when preparing for hearings or meetings.

- Chronological Order: Arrange documents in chronological order. This will help you track the progression of your case and ensure that you present information logically and coherently.

- Summarize Key Points: Create a summary document that outlines the key points of your case. This summary should include the main arguments, relevant laws, and a timeline of events. Having this overview at your fingertips can be invaluable during hearings.

- Document Everything: Keep a detailed record of all interactions related to your case. This includes phone calls, emails, and meetings. Documenting these communications can provide crucial evidence and help refresh your memory about important details.

- Gather Evidence Methodically: Collect all evidence that supports your case, including photographs, contracts, and witness statements. Ensure that each piece of evidence is clearly labeled and annotated to explain its relevance.

In addition to these strategies, consider utilizing digital tools for organization. Software applications and cloud storage can help you keep your documents secure and accessible from anywhere. Digital organization can also facilitate easy sharing of documents with other parties involved in your case.

Another essential aspect of organizing your case is preparing for court appearances. Create a checklist of items to bring with you, including:

- All relevant documents

- Your case summary

- Notes on questions to ask or points to make

- A calendar to track important dates

By being thoroughly prepared and organized, you can present your case in a compelling manner, increasing your chances of a favorable outcome. Remember, while self-representation can be challenging, a well-organized approach can significantly ease the burden and enhance your effectiveness in the courtroom.

When to Consider Hiring a Lawyer

When navigating the complex landscape of legal matters, many individuals consider whether they can represent themselves or if they should hire a lawyer. While self-representation, known as pro se representation, is permissible in the United States, there are critical situations where seeking professional legal counsel is not just beneficial but essential. This section explores the key indicators that suggest it may be time to consult with an attorney.

- Complex Legal Issues: If your case involves complex legal principles or intricate regulations, hiring a lawyer is crucial. For instance, cases involving corporate law, intellectual property disputes, or intricate family law matters often require specialized knowledge and experience that only a qualified attorney can provide. Understanding the nuances of the law can be daunting, and an attorney can help navigate these waters effectively.

- Significant Financial Stakes: When the financial implications of a lawsuit are substantial, the expertise of a lawyer becomes invaluable. A skilled attorney can help you assess the potential outcomes, negotiate settlements, and represent your interests in court to maximize your chances of receiving a favorable verdict. This is particularly important in cases involving substantial claims, such as personal injury lawsuits or business disputes.

- Emotional Stress and Burnout: The emotional toll of managing a legal case can be overwhelming. If you find yourself feeling stressed, anxious, or burned out from the complexities of your case, it may be time to seek legal representation. An attorney can alleviate some of this burden by handling the procedural aspects and providing emotional support through the legal process.

- Unfamiliarity with Legal Procedures: Legal proceedings are often fraught with procedural rules and timelines that must be adhered to. If you are unfamiliar with these processes, it can lead to costly mistakes. Hiring a lawyer ensures that all necessary paperwork is filed correctly and on time, which is crucial for the success of your case.

- Opposing Legal Representation: If the opposing party has legal representation, it is wise to consider hiring your own attorney. Facing a lawyer without professional support can put you at a significant disadvantage. An attorney can level the playing field by providing you with the necessary tools and strategies to effectively counter the arguments presented by the opposing counsel.

- Desire for a Favorable Outcome: Ultimately, if you are serious about achieving the best possible outcome in your case, hiring an attorney is a prudent decision. A lawyer brings not only legal expertise but also negotiation skills and a network of contacts that can be beneficial in advocating for your interests.

In summary, while self-representation is an option available to individuals in the U.S. legal system, it is essential to recognize the signs that indicate when hiring a lawyer is the more prudent choice. From navigating complex legal issues to managing emotional stress, the benefits of having professional legal counsel can significantly impact the outcome of your case.

Complex Legal Issues

When navigating the legal landscape, can arise that necessitate the expertise of a qualified attorney. Understanding when to seek professional help is crucial for ensuring that your legal rights are protected and that you are making informed decisions. This section delves into various scenarios where hiring a lawyer becomes essential for effectively managing intricate legal matters.

- Understanding Legal Complexity: Legal issues can range from straightforward to highly complex. Matters involving corporate law, intellectual property, or international law often require specialized knowledge that the average person may not possess.

- Litigation and Trial Representation: If your case involves litigation or trial, the stakes are significantly higher. An attorney can provide invaluable representation, ensuring that your case is presented effectively and that procedural rules are followed.

- Navigating Regulatory Compliance: Businesses often face intricate regulatory frameworks that govern their operations. Lawyers can assist in ensuring compliance with local, state, and federal regulations, helping to avoid costly penalties and legal troubles.

- Family Law Matters: Issues such as divorce, child custody, and adoption can become complicated. An attorney can help navigate the emotional and legal complexities involved, providing guidance on rights and obligations.

- Criminal Defense: Facing criminal charges is a serious matter that can have lasting consequences. An experienced criminal defense attorney can help you understand your rights, build a strong defense, and navigate the court system.

Moreover, contractual disputes can also benefit from legal expertise. Whether you are drafting, reviewing, or disputing a contract, having a lawyer can help clarify terms and protect your interests. In addition, complex estate planning issues, such as creating trusts or navigating inheritance laws, require a knowledgeable attorney to ensure that your wishes are honored and legal requirements are met.

Another critical aspect to consider is the emotional toll that complex legal issues can impose. The stress associated with navigating these challenges alone can be overwhelming. Engaging a lawyer not only alleviates some of this burden but also provides you with a partner who can offer support and guidance throughout the process.

In summary, while self-representation may be feasible in some cases, the intricacies of complex legal matters often necessitate the insight and experience of a qualified attorney. Recognizing the signs that indicate when to seek legal counsel can make a significant difference in the outcome of your situation.

Emotional Stress and Burnout

Representing oneself in a legal matter can be a daunting task, often leading to significant emotional stress and potential burnout. The journey of self-representation, while empowering, can also be fraught with challenges that impact one’s mental well-being. This section delves into the emotional toll of navigating legal proceedings alone and emphasizes when it may be prudent to seek the assistance of a lawyer.

When individuals take on the responsibility of their own legal cases, they are often faced with a myriad of pressures. The stress of managing legal documents, understanding court procedures, and preparing for hearings can quickly accumulate. This burden can lead to feelings of overwhelm, anxiety, and even depression. The emotional weight of a lawsuit, combined with the intricacies of the legal system, can be too much for many to bear alone.

It’s essential to recognize the signs of emotional distress during this process. Common indicators include:

- Increased anxiety: Constant worry about the outcome of the case can lead to heightened anxiety levels.

- Difficulty concentrating: The complexities of legal terminology and procedures can make it hard to focus on the case.

- Physical symptoms: Stress can manifest physically, resulting in headaches, fatigue, and other health issues.

- Isolation: The feeling of going through a legal battle alone can lead to social withdrawal and a lack of support.

For many, these emotional challenges may signify that it’s time to consider professional legal assistance. Hiring a lawyer can alleviate some of the burdens associated with self-representation. A skilled attorney not only brings legal expertise but also provides emotional support and reassurance throughout the process. This support can be invaluable, especially during critical moments such as court appearances or negotiations.

Moreover, a lawyer can help in reducing the emotional toll by:

- Managing expectations: An experienced attorney can provide a realistic outlook on the case, helping to mitigate anxiety related to uncertainties.

- Handling communications: Lawyers can manage communications with opposing parties and the court, relieving clients from stressful interactions.

- Providing strategic guidance: Having a professional to strategize can help clients feel more in control and less overwhelmed by the legal process.

In conclusion, while self-representation is a viable option for some, the emotional stress and potential for burnout should not be underestimated. Recognizing when the burden becomes too heavy is crucial. Seeking the assistance of a qualified attorney can not only improve the chances of a favorable outcome but also provide much-needed emotional support during a challenging time. If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed, it may be time to reach out to a legal professional who can help navigate the complexities of your case with both expertise and empathy.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can I really file a lawsuit without a lawyer?

Yes, you can file a lawsuit without a lawyer, commonly known as pro se representation. However, it’s essential to understand the legal processes involved and the challenges you may face.

- What types of cases can I handle on my own?

You can effectively manage small claims cases and certain civil matters, like landlord-tenant disputes, without a lawyer. These cases are typically more straightforward and designed for self-representation.

- What are the challenges of self-representation?

Self-representation can be challenging due to a lack of legal knowledge, emotional stress, and navigating complex court procedures. Being well-prepared can help mitigate these issues.

- Where can I find resources to help me?

There are numerous resources available, including online legal websites, court self-help centers, and community organizations that provide guidance for self-represented litigants.

- When should I consider hiring a lawyer?

If your case involves complex legal issues or if you find the emotional toll of self-representation overwhelming, it may be wise to consult with an attorney for assistance.